Homespun Heartwarmers: Ceramics By The California Cleminsons

Makes Home the Place you want to Settle.

Are the shelves and walls in your kitchen laden with plaques, platters, pocket vases, pie birds, and other kitchenabilia festooned with such phrases? Then, odds are, you're hooked on ceramics by The California Cleminsons. These whimsical, well-crafted arti-facts of the 1940's and '50's brimming with wholesome sentiment, offer a hearty helping of the good old days, mid-twentieth-century style.

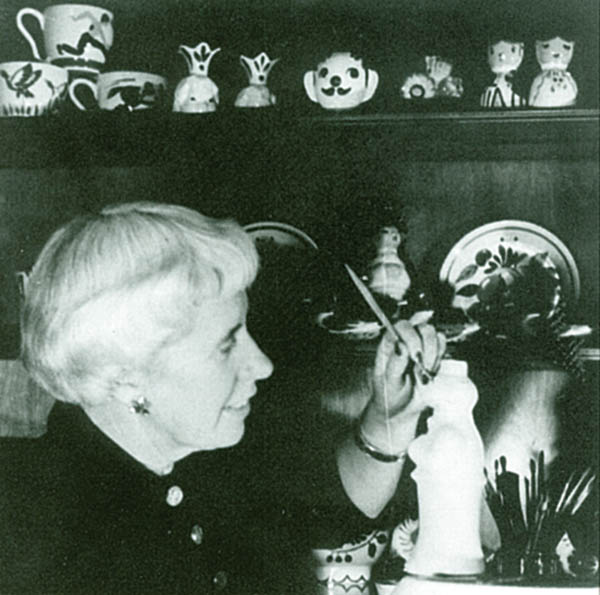

Getting underway in 1941, Cleminson Clay, like many other firms of the World War II era, owed its early success to wartime re-strictions. With overseas imports curtailed, home decorators were obliged to buy domestically. In another time, talented hobbyists like Betty Cleminson might have resigned themselves to working at a home kiln, churning out giftware for family and friends. The war changed all that. Cleminson, and other enterprising sister ceramicists - including Hedi Schoop, Florence Ward, and Betty Harrington - saw the door to success nudged open, and flung it wide. Their diverse creative output kept America smiling throughout the war years, and well into the 1950's.

Funnel Vision

Betty Cleminson's ceramics story began in a Los Angeles studio where, as an apprentice, she learned the basics of ceramic formu-las, glazes, and the firing process. In 1940, Betty received a kiln as a Christmas gift, immediately putting it to good use in her Mon-terey Park garage. Early designs attracted the attention of a local sales representative, who offered to exhibit them at a giftware show. Interest was moderate until Betty hit on an idea that proved Cleminsons' first best-seller: a line of decorative ceramic pie birds.

In days of yore, when almost every pie was baked from scratch, perky pie birds were an absolute baking necessity. Developed in England in the 17th century, the birds were essentially vents or funnels, made of such heat-resistant materials as glass, china, metal, or, (fortunately for Betty Cleminson), ceramic. The function was simple: through an opening in the top, the pie bird vented steam as the pie was baking. A hollow interior and arched base provided an outlet for bubbling juices, and kept the top crust from be-coming soggy.

The earliest pie funnels were strictly utilitarian: they looked like what they were. By the mid-twentieth century, however, design-ers of all stripes had discovered pie vents as whimsical outlets for their talents. Soon, pie birds by stylists as widely disparate as Muriel Josef and Clarice Cliff filled the marketplace. The bird shape, perhaps inspired by the nursery rhyme, Sing a Song of Sixpence, with its saga of an unfortunate flock of blackbirds baked into a pie proved a natural: the bird's open beak served as the steam vent. Figural possibilities quickly expanded, however, to include everything from Pie Chefs to Pie Mammies, Pie Elephants, and Pie Dragons. Each, however, served the same basic purpose, and each was grouped under the generic header, pie bird.

For Betty Cleminson, the pie bird of choice was an actual bird, available in a variety of sizes and décor trims, and marketed as Ralphie Roosters and Patrick Pie Birds, (those names were evidently the choice of sales representatives, not the Cleminsons). Their purpose was made clear, in hang tags accompanying each bird. The tag cover proudly proclaimed, It's something to crow about! Basic instructions (place bird on top of berries, then put top crust around base of bird were followed by a sprightly Betty Cleminson rhyme:

Wait and See-

When you bake a berry pie with a bird like me,

I'll keep your oven clean, and show you what my use is,

When you serve your tasty pie, complete with all its juices!

During the early years, to meet the rising pie bird demand, Betty Cleminson farmed out their decoration as piece work. Home-makers in the vicinity bought undecorated greenware from Cleminsons, painted the birds at home (paint was supplied), then sold them back to the pottery for firing. As acclaim grew, the Cleminsons' at-home business quickly expanded. George Cleminson, a math teacher, made the logical move to a new position as the budding firm's business manager, allowing Betty to focus on the creative end. The twosome moved their base of operations to El Monte, where 150-plus full-time workers soon busied themselves turning out Betty's useful ceramic charmers. In 1943, Cleminson Clay morphed into the catchier The California Cleminsons. Piece work was now a thing of the past, but Cleminson decorators continued to be given free rein within a basic color palette, (muted pastels on a cream background), which is why no two Cleminson pieces are exactly alike.

Upstairs, Downstairs, All Around the House

With the success of their pie birds, Cleminsons explored what other options the kitchen had to offer, from salt-and-peppers, cookie jars, and string holders, to spoon rests, rolling pins, and Lazy Susans. Once exhausting the kitchen's possibilities, the Cleminsons moved on to other rooms and uses. For the sewing room, the figural salt-and-peppers Old Salt and Hot Stuff were re-imagined, (minus their pour holes and bottom openings), as sock darners. Billed as Darning Dodos, each darner boasted the logo Darn It on its front, and painted feet on the bottom. The darners' particular importance to World War II consumers was made clear in another of Betty's hangtag rhymes:

To mend our ways is dull, it's true,

But Uncle Sam says 'make it do'-

So stitch in time, else you will rue it;

Let this 'Darning Dodo' help you do it!

For the bath, there was the Gay Blade (an 1890's dandy, pressed into service as a razor blade bank); a Pinocchio toothbrush holder (the toothbrush dangling from Pinocchio's prominent proboscis); and Katrina The Cleanser Shaker Girl (fill her with scour-ing powder, and watch those bathtub rings disappear!)

For the vanity, a Bobbie Guard bobby pin holder (in the shape of a British policeman), and Willie the Watch Dogi (His tail up tight holds rings just right - and your wrist watch fits where 'Willie' sits!). And, for the laundry room, Betty came up with one of Cleminsons' top sellers: Sprinkle Boy, an oft-imitated, Oriental-themed clothes sprinkler - a must-have in those pre-steam iron days.

Designed to Please

Although they served practical purposes, what really drew buyers to Cleminson ceramics were Betty's colorful, almost childlike designs. Shapes were cozily familiar and nostalgic - tea kettles and bean pots, crowing roosters, and nesting birds. Colors were bright, with broadly drawn detailing. The hand-lettered mottos, composed by Betty, added to the homemade touch. Those messages were always cheery, as if stitched on a sampler - (Harmony and Understanding Feed the Flame of a Happy Hearth) - or laced with simple humor (an egg cup marked For A Good Egg). And, those who saw more than a hint of Pennsylvania Dutch folk art influence in Betty Cleminson's designs were right on the money; her personal ancestry found expression in her art. That ethnic touch played a ma-jor role in the success of Cleminsons' 1950's Distlefink line. Ceramic Distlefinks (Pennsylvania Dutch for a hedge bird), of decorated white or brown, were fashioned into everything from bread trays to gravy bowls.

With imports resuming after the war, Cleminsons found itself in the same predicament as every other domestic ceramics firm. Overseas manufacturers could produce products similar in theme, (if not quality), much more cheaply. In the late 1950's, attempting to stay ahead of the design curve, Cleminsons employed the talents of designers Hedi Schoop and Barbara Willis for a series of mod-ernistic design experiments. Cleminsons' signature spin on the homespun - lovebirds perched atop ruffled cookie jars labeled Mother's Best, coffee mugs inscribed No Grounds For Divorce - gave way to lab beaker-like vases with grayish glazes and mot-tled, veiny overglazes. It may have been modern, but it wasn't Cleminsons.

In 1963, unwilling to further compromise their unique stylings, Betty and George let the Cleminson kilns run cold. California Cleminsons was no more - but its friendly output remains popular to this day, still ready to delight the eye, and warm the heart.

Text and Photos (except as noted) by Donald-Brian Johnson.

Editor's Note: Donald-Brian Johnson, co-author of numerous Schiffer books on mid-twentieth century design, is also a ce-ramics advisor for the Schroeder's and Antique Trader annual reference guides. His upcoming book Postwar Pop in-cludes more on the California Cleminsons. Please address inquiries to: donaldbrian@msn.com.

Cleminson figurines courtesy of Marlene Buthmann.