Old Seed Catalogs Combined Science, Marketing, Printing Arts

Mail-order gardening may seem like a modern phenomenon, but in fact mid-winter shopping for seeds and plants dates back at least a couple of centuries in this country, to the beginnings of the United States and its postal service.

One catalog publisher, David Landreth of Bloomsdale, Pennsylvania, started shipping seeds by mail in 1784, and claimed George Washington as a customer. The oldest known U.S. seed catalog is a broadsheet issued by Bernard McMahon of Philadelphia, also in the 1700's.

A reproduction of that McMahon document hangs on the office wall of the Andersen Horticultural Library of the University of Minnesota Landscape Arboretum in Chaska. But the Andersen Library is also the home of a big collection of original gardening catalogs - close to 100,000 wholesale and retail catalogs, dating from the mid-1800's to present.

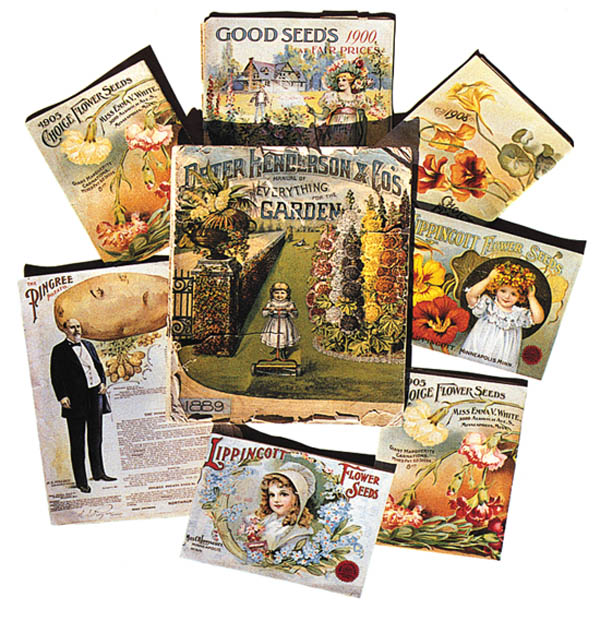

Like the library's collection of antiquarian books, these catalogs are important to researchers tracing the history of world horticulture. But many of the old catalogs are also excellent examples of the printer's art, advertising their dazzling asters and succulent tomatoes in bold, beautiful color lithography. They provide a peek into the culture of their times, too, through their often-chatty prose and sentimental illustrations.

Evy Sand, library assistant, is in charge of the special collection of mail-order catalogs, under the supervision of librarian Richard Isaacson.

Sand started as a volunteer in 1974, taking on a new project for the library: helping find plants and seeds for arboretum patrons. In other words, we at the library could find a source for something existing on the grounds, and help people purchase it, said Sand.

That's the concept behind the Source List of Plants and Seeds, a compilation of current gardening catalog offerings from hundreds of sources.

As the years went by, the old catalogs went into a historical file, which eventually took on a life - and uses - of its own. We've had people call from out of state for us to do background searches, said Sand. For example, a librarian got a question from Colorado, and they wanted to know the parentage of this squash. He found it in a 1933 North Dakota catalog.

Besides veggie genealogy, early catalogs often give researchers glimpses into early landscape design, through photos or drawings intended to show gardeners the uses of new plants. Old catalogs are more explicit about such landscaping than new ones, said Sand.

Those were the days when seeds could be purchased for 3 cents to 10 cents a packet, and the illustrations on the packets were nearly as pretty as the resulting flowers and foodstuffs. This is well illustrated by two finds donated to the Andersen Library: a wooden display case full of seed packets from the Gate City Seed Co. of Keokuk, Iowa, dating from around 1910 to 1920, and a vintage salesman's sample case from the Jewell Nursery of Lake City, Minnesota, a company that's still around.

The library has collected catalogs from every state in the United States, but Midwest seed and plant distributors play a prominent role. Northrup King & Co. of Minneapolis, Oscar Will & Co. of North Dakota and L.L. Olds of Clinton, Wisconsin are among the region's dealers represented.

These dealers catered to farmers, selling seed by the packet or the pound. Their catalogs boasted hardy northern-bred strains of grains and varied vegetables. They testify to the diversity of Midwest farm products in the days before fast transportation and refrigeration, when fresh produce consumed in a region was grown in that region.

A study of old catalogs also reveals a phenomenon of local entrepreneurship: the Three Seedwomen of Minneapolis. In 1891, Minneapolitan Carrie Lippincott mailed her first catalog in what was to become, literally and figuratively, a groundbreaking business, based at 319 Sixth Street, South. Lippincott is reputed to be the first seed seller to target women buyers, the first to specialize in flower seeds, and by her own proclamation, the Pioneer Seedswoman of America.

Working with her mother and sister, she created a thriving trade based on hard work, hands-on gardening experience, and a shrewd sense of marketing. Her five-inch by seven-inch catalogs were colorful sales tools with a personal touch. In her chatty introductions, where she updated customers on the doings of her family, she referred to the catalogs as annual Greetings. Their lithographed covers, picturing idealized children surrounded by colorful flowers, did in fact look more like greeting cards than typical catalogs of that time.

That personal touch apparently appealed to customers. In 1911, she wrote in her catalog, I wish it were possible for me to write a personal letter to all who have written me such pleasant and encouraging letters this past year. But that is impossible for I have received hundreds of them, and I thank you all for my mother, my sister and myself...

Success bred competition. Miss Emma V. White, also of Minneapolis, took up the mail-order seed trade in 1896, imitating Lippincott's catalog format but adding a few innovations of her own. Her 1900 catalog's cover had an illustration in obvious imitation of Palmer Cox's popular Brownies characters; later mailings had beautiful wraparound cover illustrations in that rich color found only in printing at its pre-World War I peak.

Then there was Jessie R. Prior, who inspired a bit of controversy in her day. Starting in 1895, she built a flower-seed business that occupied an entire block of Third Avenue South in Minneapolis by 1905. She claimed to have the only seed testing grounds in the West, located on the shores of Lake Minnetonka. By 1907, the Jessie R. Prior Flower Co. had disappeared from city listings, but not before drawing some fire from its competition.

Lippincott began publishing her picture in her catalog beginning in 1899, explaining that a number of seedsmen (shall I call them men?) have assumed women's names in order to sell seeds. White countered a few years later with the protest, I am a real live woman and I give personal attention to my business.

Prior's available catalogs are silent on the gender issue, and her business was listed under her husband's ownership for its first five years of operation, so she's considered the most likely target of this accusation. But it's also true that few of her catalogs are available in the library's collection, and there really was a Jessie H. Prior who lived in Minneapolis until her death in 1960, according to city records.

In any case, imagine an industry in which, a century ago, a male businessman could do better by pretending to be a woman. Quite a turnaround.

And these mail-order dealers did an impressive volume of business. In one of her introductions, Lippincott announced that she had shipped a quarter-million copies of her 1898 catalog. Based on census data of the period, that means about one in every 60 households in the nation was on Lippincott's mailing list.

The catalogs of the Three Seedswomen were showcases for their publishers' personal style. The farm-oriented catalogs were equally showy, though, sporting big 8 x10 color illustrations of featured fruits and vegetables on their covers and in interior illustrations.

One intriguing Northrup King catalog cover, circa 1909, is designed like a political cartoon, depicting lucky seed buyers in a birchbark canoe laden with N-K's Sterling Seeds, confidently steering around treacherous rocks labeled Inexperience, Ignor-ance, Carelessness and Exaggeration. Another Midwest dealer, Oscar H. Will of Bismarck, North Dakota, sold via a rather drab monotone catalog until 1908, when he jumped on the color bandwagon with a bold color illustration of a vegetable still life. In later Will catalogs, the cover illustrations featured respectful Indian themes as the company turned to specializing in seed corn.

Contrast these with the oldest catalog in the Andersen collection, an 1844 mailing from the aforementioned David Landreth, a 36-page booklet with a dull text only cover and discursive, but impersonal, product listings.

Where do all these old catalogs come from? Many are donated, and the library has a friend in the collectible paper field who scouts out material, but a few are purchased for a pretty penny to fill nagging gaps in the collection, said Sand. Outdated gardening catalogs are generally scarce. Usually they're the first things burned when you clean out the house, she said.

It's one of the biggest collections of this kind of ephemera around, and probably one of the most accessible, too. It's open to researchers during regular library hours, 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Monday through Friday, 11 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Saturday and Sunday, except holidays. You can also contact the library through the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum, 3675 Arboretum Drive, Chaska, Minnesota 55318-9613.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Reprinted, with permission, from The Old Times, newspaper, a monthly, Minneapolis, Minnesota-based publication about antiques and collectibles, distributed at antique shops and shows in Minnesota, Wisconsin and portions of Iowa and Illinois, and all over North America by mail subscription. For more information, contact them at P.O. Box 340, Maple Lake, Minnesota 55358; E-mail: oldtimes@theoldtimes.com; or visit online at www.theoldtimes.com.

Images courtesy of Anderson Horticultural Library, Minnesota Landscape Arboretum. Richard T. Isaacson, Bibliographer and Head Librarian.