Rose O’Neill’s Winsome Kewpies

From the mid-1910s to the 1930s, most little girls prized possessions included a Kewpie doll. The little, winged, smiling cupid usually had a special spot someplace in the bedroom, often on the bed.

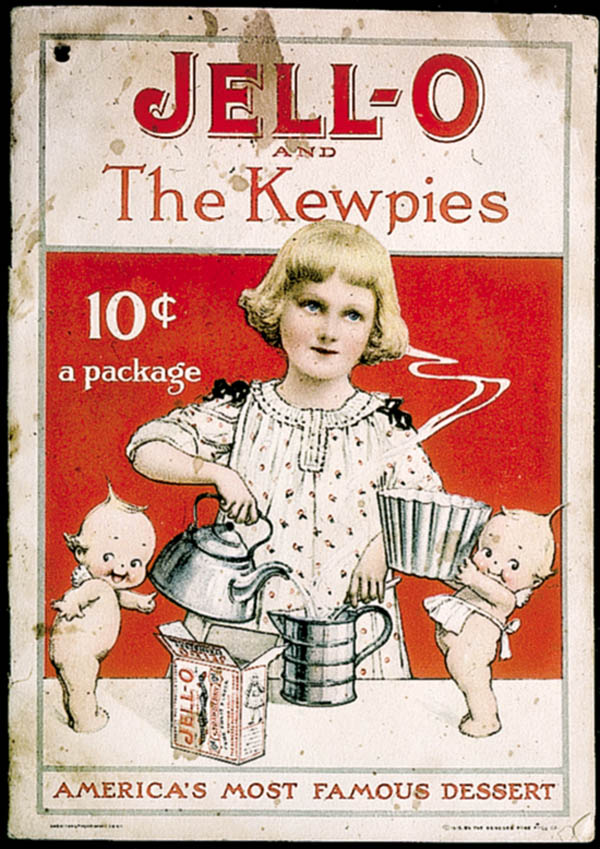

An endless number of collectors have been fascinated by Kewpies and their creator, Rose ONeill. Her Kewpie dolls and paper toys are major hobbies today, but everything ONeill ever designed in the image of her beloved Kewpies is eagerly sought. Collecting inter-ests also encompass a rather large group of advertising booklets, premiums and commercial artwork.

Rose Cecil ONeill was born June 25, 1874, in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Before she was even 16, Rose had become a success-ful freelance artist, selling cartoons and illustrations to Punch, Truth, Harpers, Life and other leading humor and general magazines of the day.

Her career continued to improve, and soon she won a full-time job with the prestigious Puck, a leading American publication. She left a few years later and resumed her successful freelance career as a book and magazine illustrator and cartoonist.

In 1909, with her sister Callista as companion and secretary, she rented a large studio apartment in the Greenwich Village section of New York City. The sisters remained there for nearly three decades. Rose, now twice divorced and vowing never to marry again, lived a slightly madcap lifestyle. Her Kewpies eventually earned her well over a million dollars. Nearly as fast as the money came in, it was spent on family, friends, and in support of countless struggling artists. It is said she was the inspiration for the popular song of the era, "Rose of Washington Square."

Success came to ONeill in part by her borrowing of ideas from Palmer Coxs Brownies. Her first Kewpies were used to decorate some verse appearing in Ladies Home Journal in 1905. Edward Bok, legendary editor of the magazine, convinced Rose to use her cheery, tiny cupids in illustrated stories. The first page of Kewpies, accompanied by her own verse, appeared in 1909. Public reaction was immediate and favorable. Americans fell heads over heels in love with the endearing Kewpies.

Other magazines began enticing ONeill with large monetary offers. In 1910, she went to Womans Home Companion and did the now famous "Dotty Darling and the Kewpies" series. In 1913 came "Kewpie Kutouts," a new kind of paper doll (with fronts and backs!). Four years later Good Housekeeping lured Rose and her Kewpies to its pages. In 1925, she returned to Ladies Home Journal, where her "Kewpieville" series debuted. During 1928 The Delineator published five of her Kewpie series.

The sweetness and cute antics of the Kewpies captivated children and adults alike. Soon readers were begging for real Kewpie dolls to hold and to love. The tidal wave of requests convinced Rose and, correctly sensing the potential profits to be made, she began mak-ing plans. Wiser that most other artists and illustrators, she patented and copyrighted her unique Kewpie creations, including the dolls.

The first Kewpie dolls came out in 1913. One of the most popular dolls of all time, millions of them in all shapes and sizes have been manufactured and sold for nearly a full century. The earliest were made of bisque. Later came composition, celluloid, plastic, and beginning in the 1960s, vinyl. Numerous other materials, among them rubber and wood, have also been used.

The first dolls were imported from Germany by George Borgfeldt and Company of New York City. Rose herself had gone to Ger-many to mold the first nine statuette designs and to oversee the initial manufacturing of them.

America quickly caught Kewpie fever, and thirty factories in Germany were kept busy trying to meet the demand. When World War I erupted, the American toy industry took over production, as they did with most other toys and dolls formerly made in wartorn Europe.

Kewpies were unique. They tickled our fancy and became far more than just cuddly toys for children. Adults, especially during the 1920s when they adorned many a Model T and other autos, used them as mascots, talismans, and good luck charms.

The passion for Kewpies has continued to the present time. In its 1946-1947 catalog, for instance, Sears offered 12-inch composi-tion Kewpie dolls for $2.58. In the 1980s, many mail order catalogs listed full lines of dressed Kewpie dolls, such as brides and grooms, ice skating couples, and birthday companions. In recent years, some of the television shopping networks have regularly sold Kewpie dolls and figurines.

Rose ONeill became wealthy from the royalties she received from her dolls and other Kewpie-related products, her artwork, and the extensive promotional use of the Kewpie name and image.

In 1914, Campbell Art Company, Elizabeth, New Jersey, began marketing "Klever Kards" of ONeills Kewpies. When folded across the middle with part of the illustration punched out, the result was a stand-up card with a die-cut design popping out at the top. Initially, Campbell offered 26 "Klever Kard" designs for everyday use; 15 more, including some with a Christmas theme, were added to the line the following year. "Klever Kards" were on sale in the nations five-and-dimes, department stores, gift shops, and all sorts of other retailers for about a decade afterward.

From 1915 onward into the 1920s, Rose ONeill created about 100 different postcards, each printed in tens of thousands of copies, and aimed at holiday and general off-the-rack sales. Most were printed by the Gibson Art Company, Cincinnati, the nations oldest and one of its most important publishers.

Collectors also remember ONeill for her Jell-O magazine ads and premium booklets, and for her Kodak camera and Edison phono-graph efforts. For over a half-century, many of the leading magazines featured countless advertisements drawn by her.

In 1917, ONeill syndicated a Kewpie Sunday comic strip to the nations newspapers; a daily strip soon followed. However, both were short-lived. The idea was later revived in 1933, when King Features convinced her to do another, this time with a continuous story line. It was moderately successful and lasted a few years.

The long and varied list of Kewpie items includes magazine covers, illustrated stories, body powders, clocks, dishes, clothing, playing cards, prints, vases, nursery chinaware, lamps, inkwells, and even wallpaper.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Rose ONeill and her Kewpies were as famous and beloved as Disney and Mickey Mouse would be in the decades following.

The illness of their mother caused Rose and Callista to give up their carefree, Bohemian lifestyle in 1937 and return home perma-nently to Bonniebrook, the 300-acre retreat in the Ozark Mountains of Missouri that Rose had purchased for her familys use many years earlier. Bonniebrook was a small piece of heaven on earth, and there she happily spent the rest of her days, passing away on April 6, 1944.

It is in the hearts and minds of those who love and fervently collect Kewpies in their many forms that Rose ONeill continues to be remembered. After all, there has never been another cutie like Kewpie!