An Examination Of Presentation Stoneware A Look At Two Lesser-Known American Items

By Justin W. Thomas - January 30, 2026

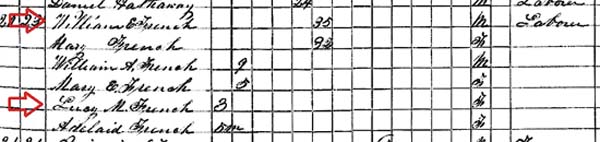

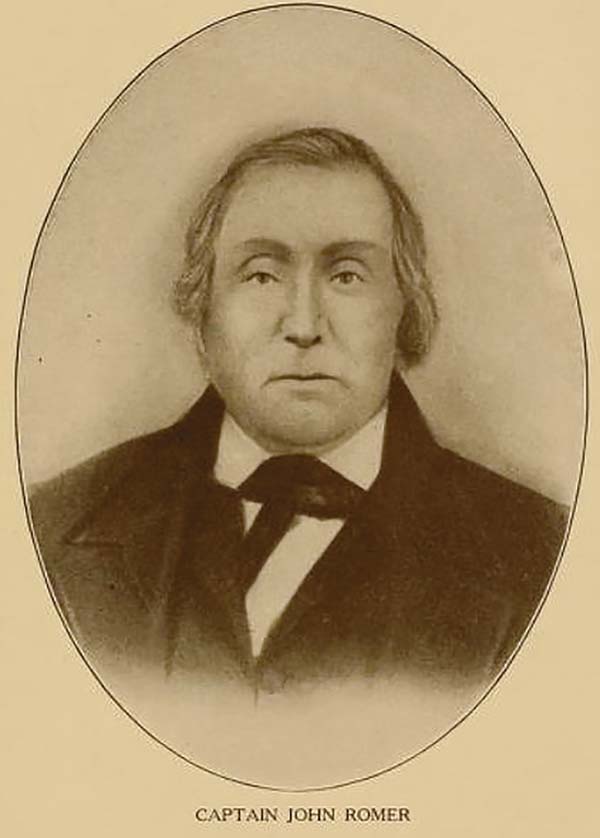

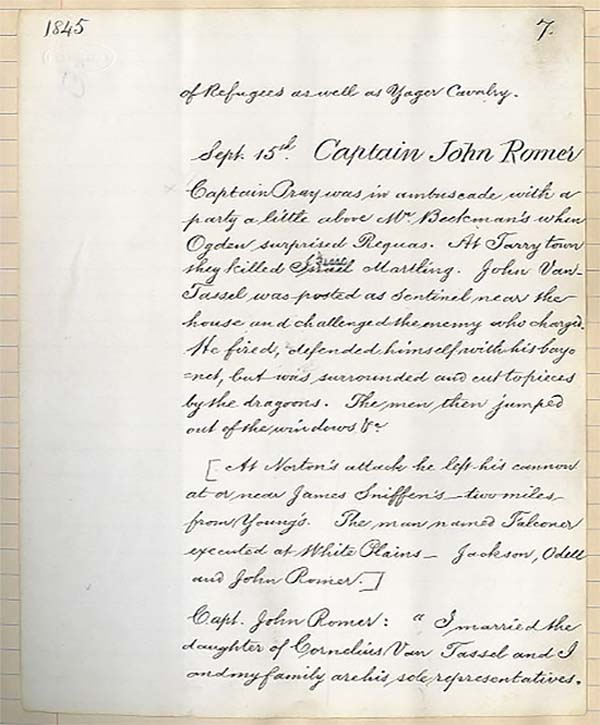

While most examples of American pottery from the 1700s and 1800s were manufactured with the intent that they would be used in the household as functional items, there were some made as presentation pieces. In some ways this personalized type of production emerged as a counterpoint to the more widely produced wares. These unique, handcrafted works sometimes focused on aesthetic appeal and skillful artistry, rather than a common utilitarian function. These types of objects were produced for family members, friends of potters, marriages, fraternal organizations and even religious purposes, etc. There are two such objects in particular that may not be widely known today, although they meet all the criteria for what might be considered a presentation object, one of which is owned by the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., while the other is owned by the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum in Lexington, Mass. The object owned by the Smithsonian is a 19th-century cobalt decorated stoneware harvest jug adorned with the hand-inscribed name L. French. The form is also a type that was produced in France, which is typically called a cruche, a pottery jug or pitcher, often with a handle and spout, traditionally used for water, wine or oil, and popular for centuries among French country potters. The Smithsonian attributes the jug to Taunton, Bristol County, Mass., which was a popular region for red earthenware production in the 18th and 19th century, as well as stoneware in the 1800s. In fact, this industry was known to have produced some heavily decorated red earthenware jars for marriages within the areas Quaker sect or denomination in the broader group of the Religious Society of Friends in America in the late 18th and early 19th century. Two of the best-known examples of this type of production are displayed today at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan, which were made for the marriage of George and Debby Purinton in 1809. The Quaker population in Bristol County was also very much part of the persecution in Salem, Mass., in the mid-1600s. It was decades later, when William Penn (1644-1710) founded the colony of Pennsylvania in 1682, as a safe haven for Quakers to live and practice their faith. Nonetheless, the brushed cobalt decorated tulip on the jug owned by the Smithsonian is a style of decoration known from the Ingalls family in Taunton, ca. 1830s to 1850s. Taunton has a rich history of stoneware production dating back to William Seaver (1743-1815) in the 1770s. Seaver is thought to have chosen the location because of the ease of moving clay by boat up the Taunton River. There were also some potters known to have worked in New Jersey who also found employment in Taunton. However, this is an unusual form of jug for Taunton. There is also no documented potter by the name of L. French working in Bristol County in the 1800s, yet there was a man named William E. French (1820-1866) with a peculiar job title in the Massachusetts State Census in Taunton in 1855. William French was born in Berkley, Bristol County, Mass., in 1820. He married Mary French (1823-1907) in Berkley on Oct. 5, 1845. The couple were living in Taunton when the 1850 United States Federal Census was taken, but French did not have an occupation listed. The 1855 Massachusetts State Census listed him as a laborer in Taunton, although no further information was cited about his profession. The 1865 Massachusetts State Census then lists him as living in Berkley working as a peddler, which is where he died in 1866. Interestingly, the couples second born daughter, Lucy M. French (1852-1907), was born in Taunton on June 15, 1852. The couple had at least seven children born between 1846 and 1863. The verbal history of this harvest jug says it was made by Benjamin Ingalls as a wedding present for L. French. The second presentation object owned by the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum is a stoneware harvest jug, inscribed, J. Romer / 1805, with Masonic symbols (all-seeing eye, sun, moon, columns, square and compasses, etc.), fish, fish hook(s) and stylized flowers. The jug may have been made in New York City, otherwise perhaps a Hudson River region potter. According to the museum, The potter who shaped and decorated this jug cut the owners name, J. Romer, and a date, 1805, under the spout. On the side of the vessel, he incised a whimsical picture of a Masonic apron into the clay, suggesting that the owner was a Freemason. John Romer, a member of Hiram Lodge Number 72 in Mount Pleasant, New York, may have called this jug his own. Furthermore, Captain John Romer (1764-1855) was born in Tarrytown, Westchester Landing, New York, on Nov. 10, 1764. He was the son of Captain Jacob (1714-1807) and Frena Romer (1725-1819). The family resided near the present Tarrytown Reservoir during the American Revolution, where Jacob and his three sons were involved with the war. John Romer was in a group of seven militia-men who captured British spy Major John Andre (1750-1780) in Tarrytown in 1780 and were instrumental in the success of the American Revolution. He later recounted his familys experiences during the Revolutionary War in an interview in 1845 with John MacLean Macdonald (1790-1863), who was a lawyer turned historian in both White Plains and New York City. The account of his handwritten interview is owned today in the New York Historical Society in Manhattan. A newspaper article published in The New York Evening Post on Nov. 27, 1897, titled, Forgotten Heroes: The Unmarked Graves of Revolutionary Patriots in Westchester County - Their Daring Deeds, recounts part of Romers life, There is one grave in this cemetery, however, which is cared for with tender solitude. It is that of John Romer, a militiaman of the Revolution, and a captain in the War of 1812, who died in 1855, at the advanced age of 92, in the house which his father-in-law, Cornelius Van Tassel, had erected on the foundations of the farmhouse burned by Captain Emerick. Captain John Romers daughter married Colonel J.C.L. Hamilton - a descendant of Alexander Hamilton, who lives in retirement at Elmsford, to whose care is due the good state of the veterans grave. Captain Romer is buried in Elmsford Reformed Church Cemetery in Tarrytown, where his grave is adorned with a masonic compass symbol. The same masonic symbol is found on the stoneware harvest jug incised J. Romer / 1805. Sources: Romer, John Lockwood. Historical Sketches of the Romer, Van Tassel and Allied Families. Buffalo, N.Y.: W.C. Gay Printing Company, Inc., 1917. The New York Evening Post. Forgotten Heroes: The Unmarked Graves of Revolutionary Patriots in Westchester County - Their Daring Deeds, Nov. 27, 1897.

SHARE

PRINT