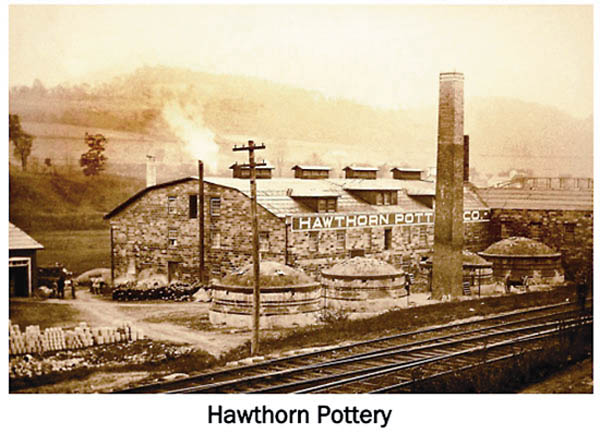

A Look At Hawthorn Pottery

Early 20th-Century Clarion County, Pa., Stenciled Stoneware

A second Clarion County enterprise, Pioneer Pottery, was owned and operated by George W. Arblaster in New Bethlehem. The third, in nearby Curllsville, was owned and operated by W. P. Hamilton in the 1870s and 80s. An examination of Pioneer Pottery will be the subject of a companion article to this, but the focus here, is Hawthorn.

The history of the Hawthorn Pottery Company begins in 1894, when W. T. Putney and E. A. Hamilton purchased the land, buildings, and pottery making machinery from Arblaster, previously mentioned, from New Bethlehem.

The local newspaper, the New Bethlehem Vindicator, reported this transaction in a dispatch quoted by one of the leading trade journals of the time, Crockery and Glass Journal: An important business transaction took place last week by which W. T. Putney of Allegheny and E. A. Hamilton, our present postmaster, got possession of what is styled the Old Spring Factory at West Millville (former name of Hawthorn). They bought the entire plant from G. W. Arblaster, who had bought from the Spring Factory creditors and fitted it up for pottery. The consideration was $3,500.It continued, The new firm will be known as Putney and Hamilton. They are to get possession of the pottery on March 1, 1894. At that time, they will start up and commence to manufacture pottery-ware. It is their intention to push the business for all it is worth, which will require them to build an extra kiln and add considerable machinery and other equipment to the plant. This they will do as rapidly as their trade will permit. Exactly what happened during the next few years is not entirely clear, but the Hawthorn Pottery Company was incorporated in 1899, with Hamilton a principal shareholder and president of the firm.

Edward Alexander Hamilton, at the time of purchase, postmaster of New Bethlehem, was the second largest holder of the original shareholders, with 30 shares out of 200. His name was shown as president on a deed dated in 1903, transferring a portion of Hawthorns real estate to the Allegheny Valley Railway Company for the purpose of building a railway siding at the pottery. Hamilton was born in 1858 and died in 1943. In addition to his role with Hawthorn and his position as postmaster his obituary indicates he also operated a foundry in New Bethlehem.

There are indications Hawthorn thrived during the first two decades of the 20th century. An agreement had been reached for the mining of potters clay from the Redbank Creek for a royalty of 20 cents per long ton (2,240 pounds). Also, more land and a railroad siding was added. By 1909, Hawthorn had offices in Pittsburgh, the nerve center of the glass and pottery trade in the region. This location served as a marketing, sales, and shipping center for Hawthorn, assuring products got sent down the Ohio river to points south and west.

While joining the astounding number of stoneware potteries that spanned for much of the states history, the later era Hawthorn joined those ranks in the declining years of stoneware production. Glass and metal containers were taking over the market. Still, it can be seen Hawthorn was not a small niche player but is reported to have employed as many as 100 workers at its prime and was noted to have produced as much at 600,000 gallons of product in a production year.

During the early 1920s, the plant passed into the control of the American Clay Products Company of Zanesville, Ohio, a holding or selling corporation that was formed in 1919, probably to control prices and assure the continuance of firms having financial difficulties.

Before closing the door on Hawthorn, lets look at what those 100 workers might have produced in such volume during Hawthorns prime. An invoice dated 1900 lists 11 products: butter pots, dutch pots, bean pots, milk pans, stew pans, mixing bowls, fruit jars, preserve jars, tie jars, jugs, and cuspidors. This list is hardly all-inclusive and clearly is oriented toward food stuffs and kitchen usage, with the exception of cuspidors, which are typically refered to as spittoons.

Other sources and records list water coolers, bread crocks, umbrella stands, pitchers, butter churns, vitrified acid jars, snuff jars, and other diverse, decorative, or specialty products. One of the best known of the latter is the half pint Kola Mint jugs used by the Kola Mint Company in Williamsport, for its Kola Mint syrup, a knock-off soda competitor aimed at the Coca-Cola market.

On its invoices, Hawthorn identified itself as Manufacturers of Bristol Glazed Stoneware. Bristol glaze was a replacement or a refinement for the older-style lead glaze process. Specifically, it originated in 19th century Bristol, England, when less toxic zinc oxide was used to replace raw lead as a flux, hence the name Bristol glaze. These glazes were also more resistant to abrasion, weathering, and chemical attack as well as giving good, bright, hues of blue and green.

The main product line were utilitarian jugs and crocks. Hawthorn jugs are found in sizes from one-half gallon to five gallons, and most crocks were from one-half to 20 gallons, though crocks of 30, 50, and even 60 gallons were being produced. The latter was reported in the following note from the Oct. 2, 1896, edition of the New Bethlehem Vindicator: Miner Knots, one of the turners in the Hawthorn Pottery, turned out some huge jars last week. The largest one has a capacity of 60 gallons. The clay used in its manufacture weighing 160 pounds. This pottery has had an unusual demand for large ware this fall.

Items marked with a capacity number in gallons usually have arrowheads on each side of the numeral as illustrated in accompanying photos. This seems to be a distinctive Hawthorn Pottery Company mark. In addition to the capacity numeral and the arrowheads, many items have stenciled upon them either H. P. Co. Hawthorn, Pa. or Hawthorn Pottery Company, Hawthorn, Pa. All marks are bright cobalt blue, which contrasts nicely with the light grey glaze on the clay, the most common color for Hawthorn stoneware. A considerable number of jugs and crocks were marked only with the numerical capacity of the container and with the ever-present arrowheads. Capacity and decorative adornments were found only on items larger than the most common gallon and half-gallon crocks and jugs, starting at gallon and a half crocks and jugs and possibly all the way to 60 gallons.

A number of crocks and jugs were glazed with a dark brown top and a light grey bottom, both by Arblasters pottery as well as those from Hawthorn. A few items, generally the larger crocks or jugs, have some added décor in the form of stars, brackets, or teardrops around the number designating the capacity.

While H. P. Co. Hawthorn, Pa. or Hawthorn Pottery Company, Hawthorn, Pa. stencils were applied on much, if not all, of Hawthorns production, additional custom-stenciled products were produced for a number of customers and merchants whose businesses found a benefit from using and displaying stoneware promoting their business name and locale. Examples of these hail from businesses in Pennsylvania, Maryland, New Jersey, and New York, as shown in one of the accompanying photos.

Hawthorn, in Clarion County, is located three counties too far to the west of what would be described as Central Pennsylvania by Jeanette Lasansky in her 1979 treatment of more than two dozen potteries in that 12-county area. This excellent work is known to all pottery collectors and titled Made of Mud Stoneware Potteries in Central Pennsylvania, 1831-1929.

Lasanskys detailed description of the day-to-day operations of those potteries and their owners and employees illusrates the kind of issues dealt with during the operation of Hawthorn. Lasanskys work gives the reader a greater appreciation of the skills and effort required to produce these items, which, in many cases, are highly collectible today. With the majority of Hawthorn pieces being from the early 20th century and semi-prolific in numbers, the work represents both a regional collectible and accessible entry point for beginner collectors.

Photos courtesy of the author.