Fanciful Curiosities For Collectors - Uncovering The Hidden Mother (And Father) Photographs

In the most basic hidden mother examples, infants were posed with their mothers holding them in such a way that the children were supported long enough for the photos to be taken, and moms were positioned in ways that would allow them to be cropped out or hidden by mats. A mom's arm or hand is often visible, and in some examples a mom's face is seen peripherally at the photo's side, in rare instances literally "de-faced," that is, scratched or penciled out.

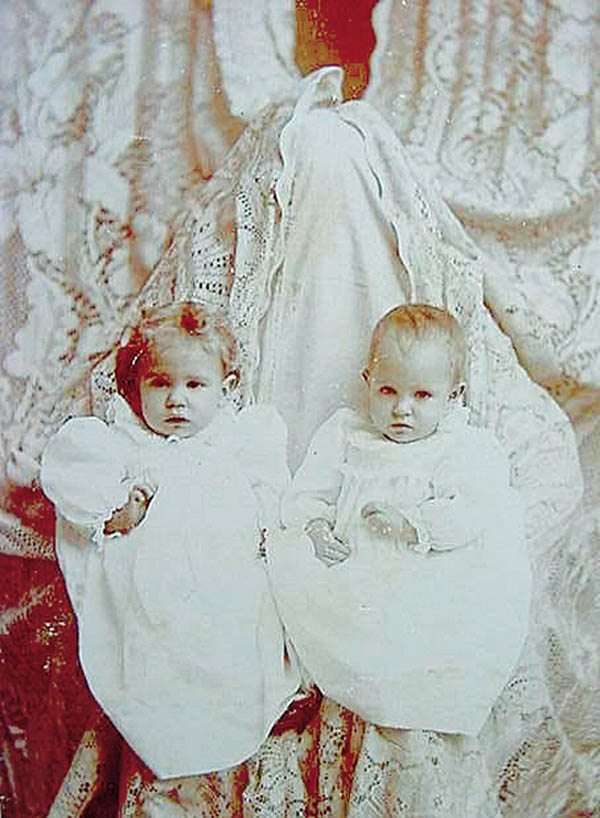

In a more dramatic category of hidden mother photos, the mother was "disguised" with a curtain or drape placed over her head and body while she held her child for the photograph. Mats were used to crop out most of the mother's veiled presence in the photo, leav-ing only enough drapery to appear as backdrop material. Removing mats in such photos reveals bizarre apparition-like figures standing behind their children or seated with the children on their laps. These shrouded, ghost-like figures are decidedly creepy and Halloween-ish, and they are especially collectible when the mother has not been cropped or matted and appears in full form.

An extremely rare type of hidden mother photo shows a posing chair with sections cut out in the back. Such "props" allowed the mother to kneel or squat behind the chair, insert her arms into the holes, and hold her child in a seated position for the duration of the exposure time. In these very uncommon images, the mothers' hands are sometimes seen holding the children. Photographers occasion-ally captured glimpses of the moms' stooped (occasionally draped) figures behind the chairs.

Despite some rather eerie-looking images, the "why" of hidden mothers in early photographs is not at all mysterious: very young children needed support while they sat for photographs because the fraction-of-a-second shutter speeds that we take for granted today were unthought-of during the nineteenth century. Even when adjustments to the sensitization process and lens improvements changed camera speeds from an initial ten-twenty minutes to several seconds, the process of posing subjects and exposing a photographic plate took some time. There was no such thing as a "snap" shot, which meant that the subjects had to sit or stand completely motionless during exposure or risk spoiling the photograph by making it blurry. In many Daguerreian era photographs, people were conveniently seated or propped against chairs or tables to maximize the likelihood of a sharply focused image. Headrests (u-shaped devices attached to chairs) or heavy iron braces and stands were also used to keep photographic subjects stationary during exposure.

Children were often tied to their seats with sash-like restraints to keep them still while their photographs were taken and, during the early 1900s, Fred Pohle invented a metal baby holder for photographers to use. Manufactured by the Pohle-Wener Manufacturing Company of Buffalo, New York, the apparatus was exhibited at the 1908 New England Photographic Convention. Wilson's Photo-graphic Magazine (1908) described it as "a very neat little device, folding up into a small space. In use it is not visible, as the baby's dress can be dropped, over the entire apparatus. It does not disfigure furniture in any way, as it is attached to a chair, for instance, by means of a thumb-screw fitting into a small female screw sunk flush in the chair. The saving in plates effected by its use will pay for one in about a month, as Mr. Pohle has figured out. Two or more can be used for group pictures." Although advertisements claimed that the holder was safe, invisible, long-lasting, and capable of holding children up to six years of age, it looked like an instrument of torture that no doubt terrified small children. Sensitive children, easily frightened children, and infants in particular, could not be ex-pected to sit chair-tied or metal-braced in strange places, in front of cameras, and with unfamiliar photographers while their moms stood a distance away. The only thing likely to keep a child calm and still in such circumstances was a mother's close presence, and in order to get a photograph of the child alone, the mother needed to be near but hidden from the camera - hence, in quirky Victorian fash-ion, the hidden mother photograph evolved as a photographic phenomenon.

There were also social and psychological reasons for infant photography and hidden mothers. During the mid-nineteenth century, as photography swept the world, industrialization saw an unprecedented change in labor economics, the advent of a non-manual laboring class, and dissemination of humanitarian ideals in regard to children. Inspired by Queen Victoria's example, the concept of "family" was raised to the status of secular religion; and Victoria's ever-increasing number of children generated cultivation of the "estate" of childhood as a social refinement that members of an upwardly mobile middle class gladly adopted. As children enjoyed elevated rank among family members and within society in general, it became de rigueur to have children photographed, and parents flocked to photo studios.

In some rare photos the hidden parents appear to be fathers. The masculine hands, arms, and hints of clothing observed in such photos may have belonged to photographers' assistants, but speculation persists that hidden fathers were spouses of deceased moms and were having photos taken of their infants as their wives would have done had they survived.

Death was an abiding preoccupation among the Victorians, and high infant mortality rates led to an elegiac motive for photograph-ing young children. Sadly, infant survival was hoped for but not necessarily expected during the nineteenth century. In England, be-tween 1848 and 1872, the mean annual death rate (per million living) for male children aged one through four was over 36,000 - and that figure included only recorded male children. High child mortality rates meant that fashionable post mortem photographs (photo-graphs of the deceased) were often images of children - especially important when no previous photos existed and death views were the only way to preserve children's features for family memory. In some rare and poignant Victorian memento mori images, a hidden mother's hands or arms cradle her dead child.

While antique hidden mother photographs are not common, they are seen at shows and estate sales, and they even have their own category on eBay. Sticker prices generally range from as little as $5 (for basic examples) to a few hundred dollars (for rare, exceptional, and post mortem photos). Daguerreotypes and ambrotypes are the oldest and are normally more costly, while tintypes, cartes de visite, and cabinet photos are typically less expensive, depending on subject matter, rarity, and condition. Values are still collector-friendly with the majority of hidden mother photographs selling for under $50, so now is a good time to begin or to build a collection.

Note: For additional information on pioneer photography and daguerreotype cases, see Photographic Cases: Victorian Design Sources 1840-1870 by Adele Kenny (Schiffer Publishing).