Privileged Young People: The Ads In St. Nicholas Magazine, Circa World War I

As I write this, one such bound volume for 1891 has a bid on eBay of $9.95; four lovely Christmas issues from the 1920's are seeking bids of $24.95 each. In fact, individual issues of St. Nicholas - and various other journals - routinely sell for more than bound volumes including those issues. This peculiarity results from actions taken by those who bound these magazines: the removal of covers and all of the advertising that appeared on pages separate from editorial material. None of the librarians whom I queried at my university library - and at a famous Delaware research library - had a satisfactory explanation of this practice or could point me to any research on this question. (It is possible, of course, that leaving out the advertising made volumes equivalent to TV specials that boast that there will be no commercial interruptions!)

Magazines represent the most accessible sources of primary documentation of past ages. As an art historian specializing in late-19th-Century American art and material culture, I have made extensive use of journals preserved in research libraries. Nevertheless, when I was lucky enough a few years ago to acquire a number of issues of St. Nicholas, I was startled by their profuse advertising. The countless bound volumes of magazines I had pored over in libraries - including St. Nicholas - contained little advertising, and no full-page ads. Unfortunately, these tend to be the only old magazines available to scholars in most research libraries. The absence of significant advertising material in these volumes has obscured something that should have been obvious: that magazines were America's only national advertising medium before radio came along. Today, of course, both the collectors who buy and the researchers who study old magazines typically prize the advertising more than the editorial content. This advertising is the best surviving documentation available to students of popular history and material culture. Because they are missing their ads, the runs of old magazines in research libraries must be seen as useful but fundamentally misleading.

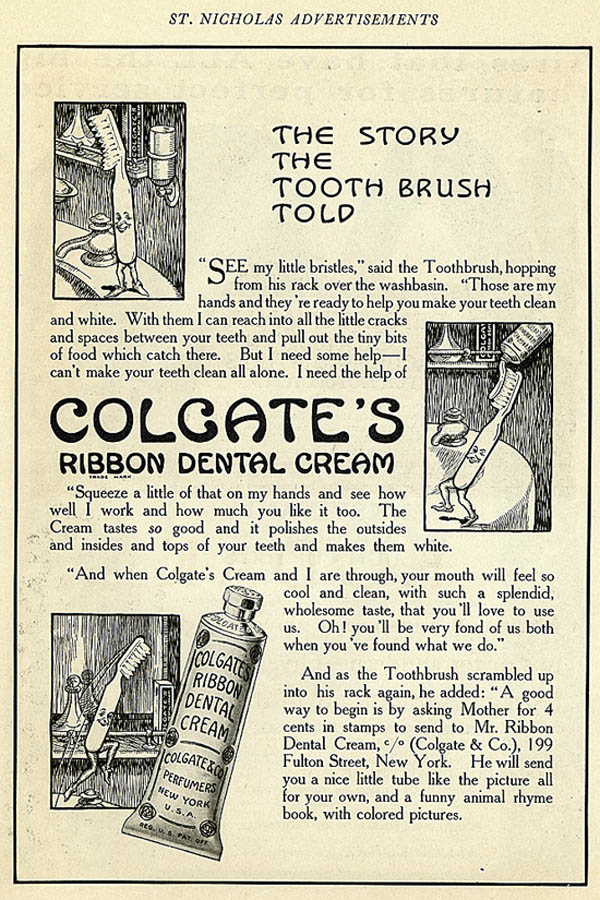

Each issue of St. Nicholas from the 1910's and 1920's is rich with ads that are both historically illuminating and eminently collectible. The remainder of this piece provides a summary overview of the kinds of ads you can expect to find. As you would expect in a magazine for children, toys and games, and food products for kids, predominate. Many of the brands offered remain prominent today.

My favorite food ad, promoting the Swiss firm Gala Peter's milk-chocolate bars (now part of Nestles), shows a pilot dropping chocolate bars from a biplane, and is captioned "A record flight from the Alps to America." (April 1911) Almost as appealing is a May 1920 ad for Nabisco, Anola, and Ramona sugar wafers, showing children dancing around a maypole in the background. Jell-o ads were ubiquitous, such as one from March 1916 that enlisted Rose O'Neill's Kewpie dolls on behalf of the Genesee Pure Food Co. (which eventually became part of the Postum Co., and then General Foods). Kellogg's Toasted Corn Flakes (July 1916), Grape Nuts, and the various puffed cereals of Quaker Oats regularly reached out to young readers. Naturally, Campbell soup advertised in St. Nicholas; the Campbell kids were rarely absent from issues. (July 1916) The Wrigley Company was another big advertiser; its fall ads regularly employed Santa themes. (December 1913).

Toys and games dominated advertising. I love the vehicles offered, which included the 1917 B-C Light Eight - the "Wonder Car for Children" (November 1916); the U.S. Dispatch Car for young America (October 1917) from the Dan Patch Co. - perhaps named for the famous race horse; and of course, the Flexible Flyer sleds that appeared regularly in fall and winter ads (December 1915). Models and building sets were mainstays of advertising. Airplane models appeared regularly. A November 1917 ad offered kids a chance to build their own 3-foot War Aeroplane, the Curtiss Military Tractor. (Other models available included the Wright biplane, the Bleriot monoplane, and the Curtiss flying boat). Ads for construction sets from Erector, Structo, Meccano, and lesser-known brands multiplied in the months leading up to Christmas. The double-page ad from Erector shown in this article (December 1916) is both particularly informative and one of the few ads to employ some color printing, which was phenomenally expensive. Toy trains from Lionel (? 1922), American Flyer, and Ives were other Christmas-time standards. During the years of World War I a number of war-related games were introduced, such as McLoughlin Bros. "American Boys State Camp." (June 1919) These ads - and those for sports shoes like Keds (June 1917) - were aimed primarily at boys. So was the ad urging children to help win World War I by becoming a "Victory Boy;" this organization sought "a million boys behind a million fighters." (November 1918)

Only a few of St. Nicholas' ads were aimed primarily at girls or were even relatively gender-neutral. Kodak's ads for its Brownie cameras occasionally show girls using them, but more often these ads resembled this one featuring boys showing off. (July 1924) Binney & Smith Co.'s ads for Crayola crayons and various games employing them, such as "Uncle Wiggley," were as neutral as ads got. So was a cute ad from the Baker & Bennett Co. for Wonder Blocks, which could be combined into numerous shapes. (October 1917) (Incidentally, the box at lower left in this ad seems a striking source for the 1950's and 1960's sculptures of Louise Nevelson, a leading American sculptor). The most interesting ad aimed at girls offered the "Western Electric Junior Range," a working, miniature electric stove upon which girls were encouraged to "cook dolly's Christmas breakfast." (December 1916) (It came as news to me that Western Electric, the manufacturing arm of AT&T, once made toys). The only dolls advertised in the issues I acquired were directed at infants. Babies could "start a Rite family" with seven dolls: Daddy, Mother, Brother, Sister, Tige, Kitty, and Bunny Rite, made of hand-painted sanitary and unbreakable ivorite - all for 25 cents. (October 1917) By stretching things one can also consider the ad for Famous Players-Lasky's version of Louisa Alcott's Little Women to have been aimed at young ladies. (February 1919) The absence of doll ads and presence of girls more often in food ads than in ads for toys and games seem to reflect gender expectations of the day. Women were responsible for feeding a family; physical activities and "creative" endeavors - and money matters - were men's responsibility.

These ads and their unfortunate omission from bound volumes show us why it is vital - and desirable - that collectors and scholars work together rather than view one another suspiciously or disdainfully. It has long bothered me that many historians view collectors as a bit eccentric and treat them with condescension. At the same time, some collectors seem indifferent to the historical significance of their treasures and refuse to share them with scholars. If, as this article contends, intelligent research in both history and material culture requires the study of original copies of magazines, which are mostly in the hands of collectors, the need for increased collaboration between collectors and scholars (not that these are mutually exclusive) seems obvious. One likely result of such cooperation will be a growing respect for collectors. It is about time that scholars begin saluting the perspicacity of collectors. After all, it was collectors, not scholars or cultural professionals - many archives still refuse offered gifts of ephemera - who first recognized the historical significance of, and preserved, the objects that scholars rely upon ever more heavily in their efforts to understand the past!