Artistic Splendor Of Tudor England To Be Exhibited At The Met

First Exhibition In The U.S. Focusing On Art Created During The Tudor Dynasty Will Feature More Than 100 Paintings, Tapestries, And Sculptures

December 02, 2022

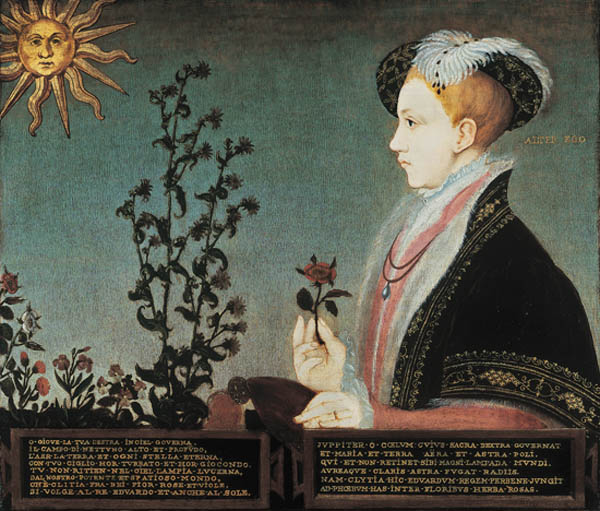

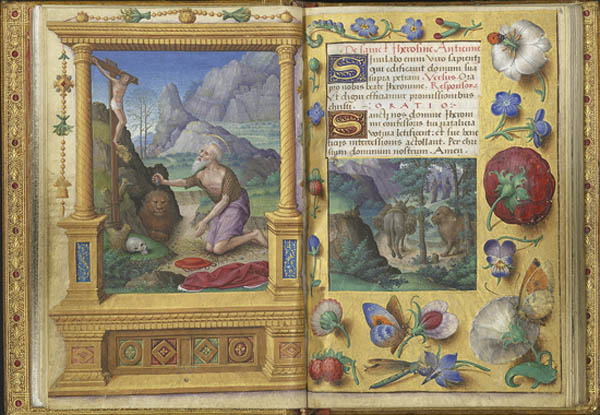

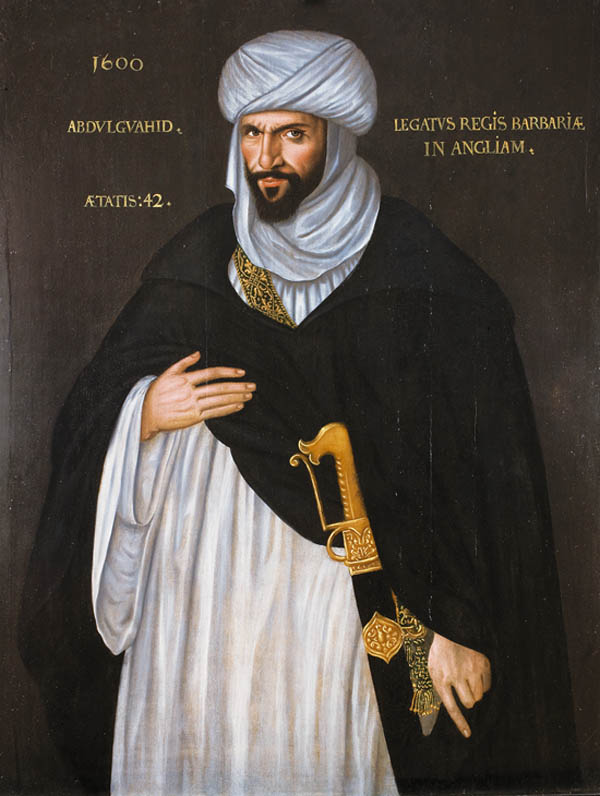

From King Henry VIIs seizure of the throne in 1485 to the death of his granddaughter Queen Elizabeth I in 1603, Englands Tudor monarchs used art to legitimize and glorify their tumultuous reigns. On view at The Met until Jan. 8, 2023, The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England will trace the transformation of the arts under their rule through more than 100 objects, including iconic portraits, spectacular tapestries, manuscripts, sculpture, and armor, from both the museum collection and international lenders. The exhibition is organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Cleveland Museum of Art, in collaboration with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. This magnificent exhibition brings the stunning majesty and compelling drama of the Tudor dynasty to life, said Max Hollein, Marina Kellen French director of The Met. By examining the wider political and societal context in which these sumptuous goods and extraordinary portraits were made, we can appreciate both their exquisite beauty as works of art and the complex and often turbulent stories they tell. Exhibition co-curator Elizabeth Cleland, curator in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, added: The sense of majesty that the Tudors crafted around themselves was so successful that, even now, we need to take a step back and remind ourselves just how tenuous their claim to the throne actually was and how many challenges they were facing. English Renaissance literature of this time, particularly the plays of William Shakespeare, continues to be world famous today, added exhibition co-curator Adam Eaker, associate curator in the Department of European Paintings. This exhibition gives us the opportunity to introduce The Mets audiences to the stunning visual arts of the period and the ways that both artists and patrons used imagery to navigate the treacherous waters of court life. Rather than an illustrated history of the Tudor monarchy, it offers a fresh look at the incredible figurative and decorative arts made or acquired for the court. Exhibition Overview England under the volatile Tudor dynasty was a thriving home for the arts. An international community of artists and merchants, many of them religious refugees from across Europe, navigated the high-stakes demands of royal patrons against the backdrop of shifting political relationships with mainland Europe. The Tudor courts were truly cosmopolitan, boasting the work of Florentine sculptors, German painters, Flemish weavers, and Europes best armorers, goldsmiths, and printers, while also contributing to the emergence of a distinctly English style. This exhibition features works of art made under the patronage of all five Tudor monarchs: Henry VII (reigned 14851509), Henry VIII (150947), Edward VI (154753), Mary I (155358), and Elizabeth I (15581603). It is organized thematically in five sections within an overall exhibition design that evokes the long galleries and intimate alcoves that defined Tudor palace architecture. Deriving their power from Henry VIIs seizure of the throne in 1485, concluding the Wars of the Roses, all five monarchs of the Tudor dynasty grappled with crises of legitimacy and succession. Beginning with a spectacular group of Italian bronze sculptures (reunited here for the first time since the 17th century) from a never-completed tomb for Henry VIII, the exhibitions first section, Inventing a Dynasty, shows how the Tudors devoted vast resources to crafting a public image as divinely ordained sovereigns, shoring up their tenuous claim to the throne. A series of portraits will introduce visitors to the five Tudor monarchs; included here are the exceptional loans of Hans Holbein the Youngers portrait of Henry VIII from the Museo Nacional Thyssen Bornemisza in Madrid and the Sieve Portrait of Elizabeth I by Quentin Metsys the Younger from the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena. The next section, Splendor, evokes the ornately layered interiors of Tudor palaces, filled with figurative plasterwork, tapestries, metalwork, and the lavishly dressed bodies of the courtiers themselves. As monarchs traveled between residences, portable furnishings transported their magnificence with them. Tapestries woven in richly dyed wools, silks, and metal-wrapped threads enveloped rooms. This section highlights the Tudor monarchs taste for luxurious imports from the continent, but also the work of local artists and newly arrived Flemish and French immigrants. Examples include Henry VIIIs personal book of psalms (British Library), featuring handwritten annotations by the king himself. Public and Private Faces spotlights the dominance of portraiture in Tudor painting and the transformative impact that Hans Holbein the Younger (ca. 14971543) had on the genre. In 16th-century England, portraits recorded status, lineage, piety, and political affiliation, as well as physical appearance. Languages of Ornament illuminates how Tudor arts combined the classical, the natural, and the neo-medieval, forming a uniquely English Renaissance aesthetic. Like other elites of Renaissance Europe, the Tudors were interested in the artistic legacy of ancient Greece and Rome. The exhibition culminates with Allegories and Icons, a collection of striking depictions of Elizabeth I, the last Tudor monarch, including the celebrated Ditchley and Rainbow portraits, on loan from the National Portrait Gallery (London) and the Marquess of Salisbury, respectively. Facing enormous pressure as an unmarried female ruler, the queen exerted tight control over her image. Her carefully vetted portraitists drew upon the elaborate allegories devised by court poets to pay tribute to the queen and her immense powers. As the Protestant Reformation had brought about the destruction or removal of religious images from English churches, most artists focused on investing the monarch, as newly proclaimed head of the church, with an enchanted and sacred authority. At the same time, printmakers created mass-produced images that celebrated Elizabeth as a protector of the Protestant cause. The exhibition concludes with a portrait, from The Met collection, of Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, a dynamic depiction of the Stuart dynasty that came to the throne after Elizabeths death in 1603, ushering in a new age of artistic styles. A fully illustrated catalogue will accompany the exhibition. Published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and distributed by Yale University Press, it will be available for purchase from The Met Store. The catalogue is made possible by the Diane W. and James E. Burke Fund. Additional support is provided by the Hata International Foundation and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation. To learn more, visit www.metmuseum.org.

SHARE

PRINT