Carl Mehwaldt: A Pioneer German-American Potter And 19th-Century Immigrant

Redware From Western New York State

By Justin W. Thomas - October 15, 2021

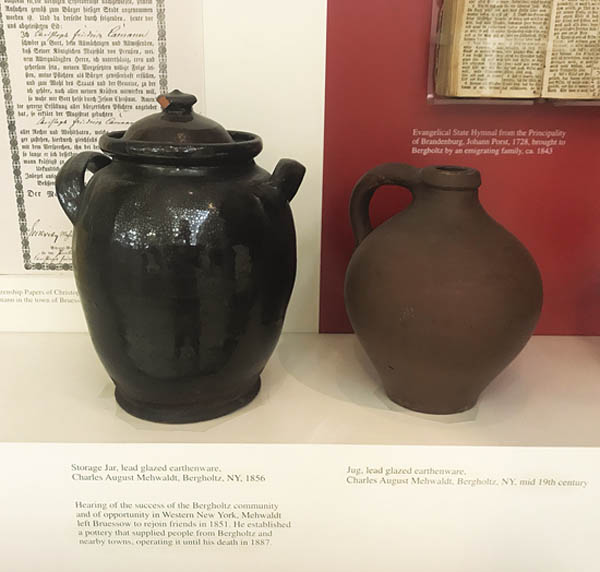

For one reason or another, I consider the career and life of Carl Mehwaldt (1809-87) to be a fascinating story. He was a journeyman potter from Germany who traveled to Russia and Lebanon to expand the knowledge of his trade. He then returned to Germany and eventually migrated across the Atlantic Ocean, landing on Long Island. He made his way through New York City, traveling northwest along the Erie Canal on a barge, before settling near Niagara Falls in western New York. The Buffalo Historical Society first published his story in 1921, followed by an article in the September 1922 issue of The Magazine Antiques. Ada Walker Camehl (1866-1939), who lived in western New York and authored some pottery books, wrote the articles. Camehls articles were also among the earliest published stories devoted to a single American potter; these stories were based on her firsthand accounts with Mehwaldts living daughter and locals who remembered the Mehwaldt Pottery from their childhood. Born May 25, 1809, in Bruessow, Prussia (later Germany), Carl Ludwig Heinrich Mehwaldt, as his birth certificate reads, has been the subject of a name dispute for decades. He is recorded as Charles in the United States Federal Census, as well as some business directories. He did have a son Charles. In a history of his life, documented and preserved because of Camehl: Mehwaldt came of a line of potters; for his father and his grandfather before him had spent their lives at the potters wheel. After he had learned the trade, young Mehwaldt, as was the custom of the country, passed several years as a journeyman potter, in search of experience. In the early 1840s, a man of wealth, Williams by name, gathered together several families from the neighborhood of Bruessow and brought the little band to the United States. They purchased a piece of land in western New York, on the Niagara frontier, cleared the timber and built a hamlet of log houses. Remembering the village from which they had come, they named the new home New Bergholz, later dropping the New. Fired by the glowing accounts, which came back to the Fatherland from this transplanted colony, a second company came together in 1851. Among this group were the potter Mehwaldt, his wife, Albertine and their children. Their voyage lasted seven weeks, and as seems to have been the not uncommon fate of sailing vessels during those years, the ship ran ashore upon a sandbar off Long Island, the passengers were rescued, and the party made their way across New York State by way of the Erie Canal, eventually arriving in Bergholz. Sometime after Mehwaldt arrived, he established a pottery business, which operated similar to other rural country potters found elsewhere in western New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia and throughout New England. But his skill is perhaps what sets him apart from some of these other potters. Mehwaldt manufactured red earthenware from the early-1850s right up until around the time he died in 1887. He must have also exported some of his wares, seeing that there was only so much demand from the small village in which he lived. He may have taken advantage of the Niagara River and shipped some of his production to communities along the waterway, such as Buffalo, where the expanding population had already reached 81,000 people by 1850. The utilitarian wares he made consisted of a wide variety of forms, some decorated with colors that resemble a Rockingham glaze, and others reportedly partially created using animal blood. He made lidded jars, pitchers, candlesticks and drawer pulls. Other forms include jugs, strainers, handled pots, cake molds, vases, chimney flue liners and flowerpots. Camehl was also able to identify that he made cups and saucers, bottles, mugs, teapots, teakettles, dishes, platters, bowls and coffee pots. Rarely is any of this pottery marked, but Mehwaldt is known to have inscribed the letter M into some of his wares. Some of the lidded forms were also inscribed with a number that matched a lid to a vessel accordingly. Interestingly, I suspect that some of Mehwaldts lesser-known production could be mistaken for wares made in Pennsylvania and other areas where there were German-American potters. For instance, Mehwaldt is known to have produced a selection of miniature dinner sets, along with toy whistles in the form of pigs, owls, roosters and birds around Christmas. He also made inkstands with penholders, a form common to Germany and Pennsylvania in the 18th and 19th century. However, after researching a lot of this material, I was compelled to learn more about Mehwaldts life. I decided to travel to the Das Haus Museum, which is a part of the Historical Society of North German Settlements in western New York, and the site of the Mehwaldt Pottery, located about 10 miles east of Niagara Falls. Not only did I want to learn more about his career, but I was determined to hear more about two special pieces of pottery he made for two of his sons after they died in the Civil War. I consider these objects to be national treasures today. The Site of the Mehwaldt Pottery I arrived at the Das Haus Museum with my nephew, Jason, and niece, Alexis, on Aug. 14, 2019. The museum is located directly across the street from Mehwaldts house and the site of his pottery. Mehwaldt was clearly a remarkable potter based on the wares that I have seen in the New York State Museum in Albany, N.Y., as well as private collections, and an object owned by the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. However, it is his lesser-known production that really sets him apart. Upon arriving to America, two of Mehwaldts sons, Charles (d. 1864) and Herman (d. 1864), became enamored with patriotism, and enlisted in the northern army during the Civil War in 1862. Neither returned home. Charles was killed in Cold Harbor, Va., on June 3, 1864, and a few weeks later, Herman died in Petersburg, Va. Likely overwhelmed with emotions, Mehwaldt decided to memorialize his sons by constructing two red earthenware wreaths in their memory. He began with a round pottery frame, 16 inches in diameter, and meticulously decorated both wreaths with hand-modeled flowers that grew around his home; each wreath was adorned in sunflowers, roses, daisies, myrtles, zinnias, water lilies and buttercups, surrounded by leaves. The wreaths were then fired in the kiln without a glaze, and afterwards, carefully painted with vibrant colors. Mehwaldt hung the wreaths in the Holy Ghost Church, only a few hundred yards from the site of his house and pottery, until the church was torn down in 1906. Where the wreaths went next is not completely known, but apparently, Ada Walker Camehl had come into the possession of at least one of the wreaths based on the information she published in The Magazine Antiques. The whereabouts of these wreaths have been unknown in recent years, but one was just rediscovered in Seattle, Wash., and has returned home to the Das Haus Museum. However, it has not been previously published that there was actually a third wreath manufactured by Mehwaldt. This wreath had resided in a local home, hanging above a doorway, until it was accidentally knocked over many years ago, breaking into dozens of pieces. It then descended through the family to the present owner, Bob Mueller, who was generous enough to come to the Das Haus Museum and share the remains of this treasure. It is currently unknown who it was made for, but it may have been made for another soldier killed in the Civil War who belonged to the Bergholz community. I also learned about a huge red earthenware chandelier created by Mehwaldt for the church; it was described as four feet in diameter, illuminated with four rows of candles, and decorated with hand-applied objects. The chandelier was eventually removed when the church was torn down, and part of it ended up in Camehls collection, but its whereabouts today is unknown. Mehwaldt also apparently manufactured stoves, similar to those made by some of the southern Moravian potters. I was surprised to see the remains of this type of production recovered from the site of his pottery, which reminded me of an intact well-published stove in the collection of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts in Winston-Salem, N.C. In Retrospect It has been published that Mehwaldt was generally a lone potter who received some help with digging and kneading clay and preparing glazes from his children and other local kids. Mehwaldt is considered to have been the only potter working at this business, although I believe I may have observed otherwise. While studying a group of handled pieces owned by the Das Haus Museum, I noticed differences in the way some of the handles were made. Perhaps Mehwaldt had different styles, but I would not be surprised to learn if there was another person employed with him in some capacity. Carl Mehwaldt was an incredibly talented potter who lived a tough life with many family tragedies. However, he remained a potter well into his 70s. Mehwaldt may have given up the potters wheel at an earlier age, but there was no one to succeed him in the business. This was reportedly a disappointment since he was a third generation potter, and he had hoped the family legacy would continue after him. But his skill as a potter and an artist should never be forgotten. He was unquestionably one of western New Yorks most talented potters, who produced some of the regions most memorable wares, some of which appear to be unique to American production today. Sources Camehl, Ada Walker. The Old Bergholz Pottery. Publications of the Buffalo Historical Society: Volume XXV The Book of the Museum, 1921. Camehl, Ada Walker. Mehwaldt, a Pioneer American Potter. The Magazine Antiques (September 1922). Lewis, Clarence O. Mehwaldt Death Ended Bergholz Pottery Era. Niagara Falls Gazette (May 26, 1965). Ketchum, William C. Jr. Potters and Potteries of New York State, 1650-1900 Second Edition. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1987.

SHARE

PRINT