Gerry Williams: Influential New Hampshire Studio Potter, Part One

By Rick Russack - October 25, 2024

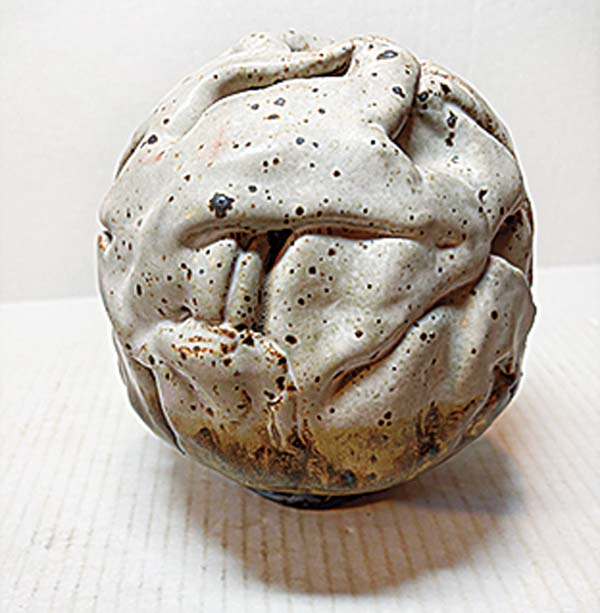

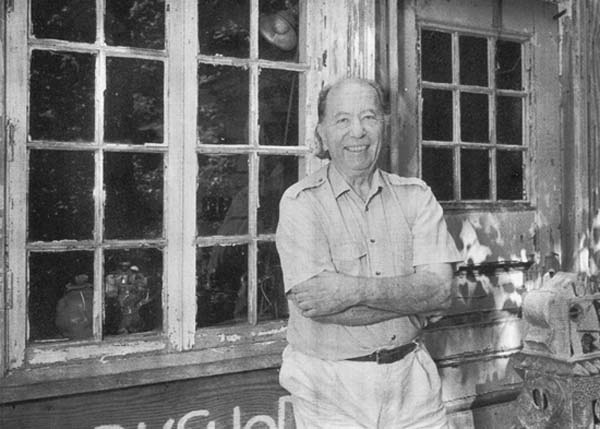

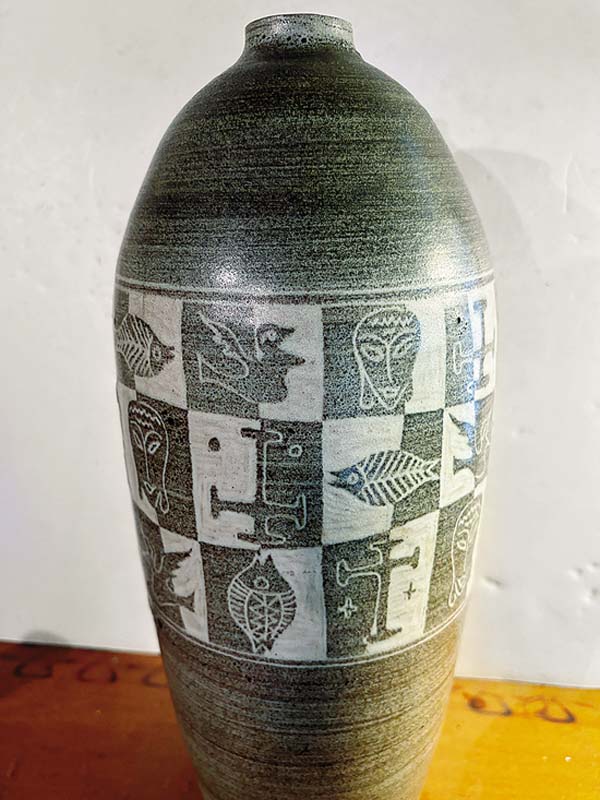

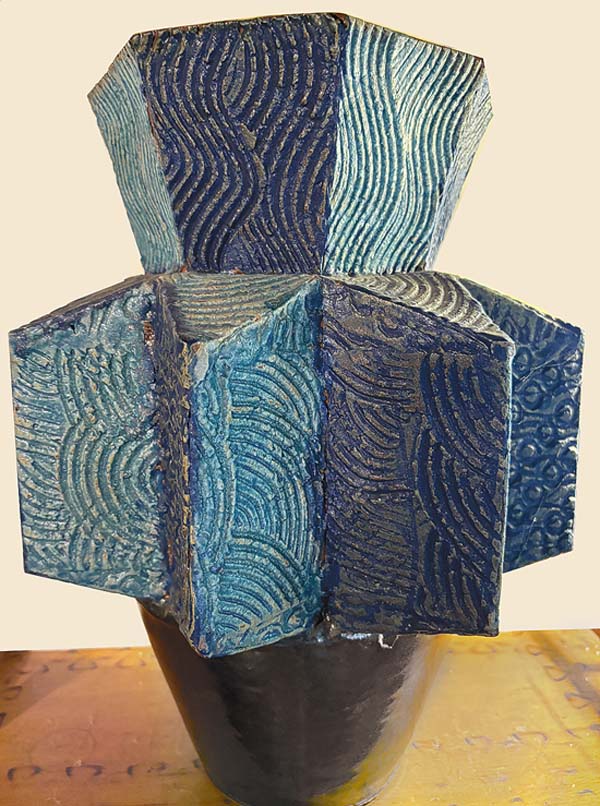

Who was Gerry Williams (1926-2014)? He was, perhaps, one of the most creative, influential and successful utilitarian/functional studio potters of the second half of the 20th century. He lived and worked in Dunbarton, N.H., for more than 50 years. There were numerous solo exhibitions of his work. His works were also included in several prestigious international shows, including one at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1969. His works are presently in several museum collections. In 1976, a documentary film was devoted to his life and work and distributed by the Public Broadcasting System. Two years later in 1978, he was interviewed for the Smithsonians Archives of American Art oral history project, one of fewer than 100 potters who have been interviewed. He would later conduct interviews of other potters for the Smithsonian. In 1998, the governor of New Hampshire designated him as the states first Artist Laureate. He was the recipient of numerous other awards and prizes. He experimented endlessly, developing hard-to-master glazes and a technique for printing photographs directly on pottery. In 1972, he founded, and for the next 30 years was the editor of Studio Potter magazine, accepting no paid advertising, which he referred to as a magazine for potters. Its still being published. He lectured extensively on the how-to of pottery making and other subjects, in this country and abroad. He taught at Dartmouth College and elsewhere. Beginning in 1973, he and his wife, Julie, hosted a series of summer workshops at their home, which came to be known as the Phoenix Workshops, bringing other well-known potters to New Hampshire to pass on their knowledge. His first studio was in a rented milk room in a barn in Concord, N.H. In the late 1950s, he and Julie moved to Dunbarton, N.H., where they had built a home and studio. His earliest pottery was made of red clay he dug himself from clay pits nearby that had been used by Daniel Clark, a Colonial redware potter. After locating and reading Clarks diary at the New Hampshire Historical Society, Williams looked to Clark as a sort of role model. Nearly every piece of pottery Williams made was signed. The early pieces, from the 1950s and early 1960s, are identified by an impressed hand, sometimes with the letters G on one side and W on the other. The surface decoration is distinctive and was not used later in his career. Williams considered himself to be a utilitarian potter, producing plates, bowls, vases, teapots, cups and saucers, casseroles, etc. meant for everyday use, much as Daniel Clark had done. In the 1970s, his work was sometimes marked with an impressed phoenix. Most pieces are marked with his incised signature, but collectors of his work should familiarize themselves with his glazes and forms as there were other potters named Williams and whose signatures can be confusing. Throughout the next 30 years, he worked mainly with stoneware and porcelain. Some of the glazes that he used were subject to almost continuous experimentation. He, and other potters of the period, were seeking to duplicate the glazes used by early Chinese potters: copper greens, copper blues, and, most importantly, copper red. These colors required hours of experimenting, both with chemical ingredients of the glazes and the firing techniques used in kilns. Studio Potter magazine published numerous articles by various potters discussing their work with these glazes. Williams would eventually succeed with these colors, but production was limited and the greens and blues are especially difficult to find today. Williams also wanted to be able to print photographic images directly onto pottery. In the 1970s, this could not be done but Williams sought the help of Edward Land, creator of the Polaroid camera and film, and eventually mastered the technique. One of the earliest examples of this technique incorporated images of his teenage daughters. Another incorporated images of Mahatma Ghandi and Ceaser Chavez, who campaigned for the rights of farm workers. Born in India, Williams was the son of missionaries. He absorbed the pacifist views of Ghandi and refused to serve in the United States military, instead serving time in jail and working at CCC camps. He was a strong believer in the Civil Rights and anti-war movements and created effigy groups relating to these events. Early in his career, his output was sold through the stores operated by the League of New Hampshire Craftsmen. From his earliest days, his work was also sold directly from his studio. As his work gained exposure through the numerous exhibitions he participated in, his market widened. Interestingly, he writes of packing his car with pottery and personally delivering it to retailers and galleries. One cant help but think of this as a continuation of how redware potters, such as Daniel Clark, sold their wares. Most was sold on consignment, with a 50/50 split for Williams and the retailer. Invoices survive that show his works were sold in Boston, New York, Baltimore, and in numerous other markets, and many were not inexpensive. Several invoices show that many of his pieces were priced at $40 (which is the equivalent of about $300 today). As his name and work became better known, some of these retailers widely advertised his work. A 1965, three-quarter page ad by Filenes in Boston (one of his better customers) in the Boston Globe was devoted exclusively to promoting his work, using his name and picturing some of his work. Through Studio Potter magazine, the Phoenix Workshops, his teaching at universities in this country and abroad, his writings and lectures, Gerry Williams was one the most influential potters of his generation. Photos courtesy the authors collection.

SHARE

PRINT