John Lockwood Kipling

By Amy Gale - December 08, 2023

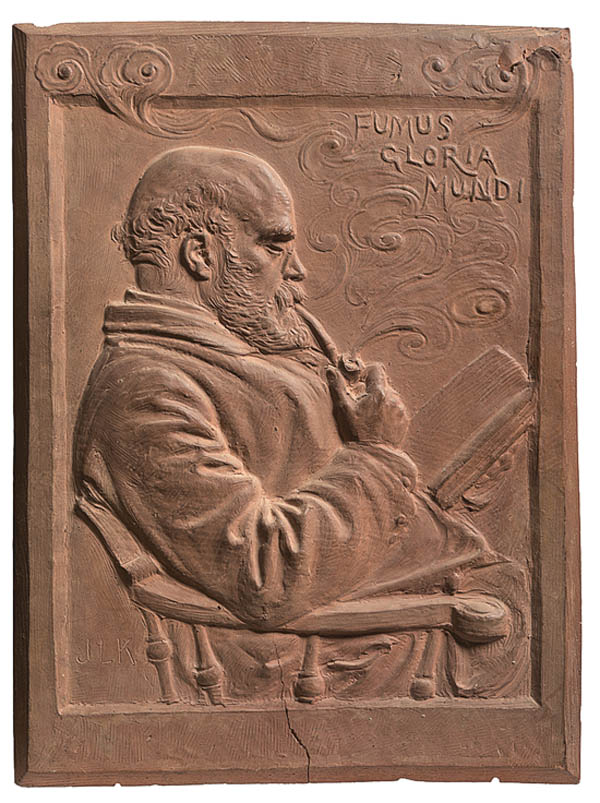

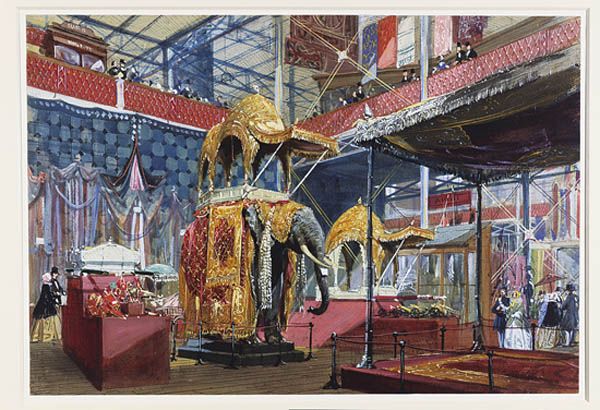

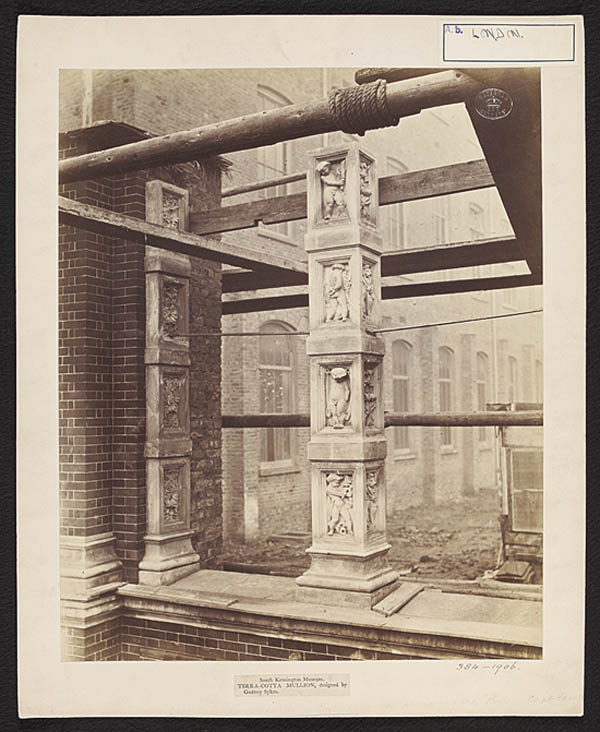

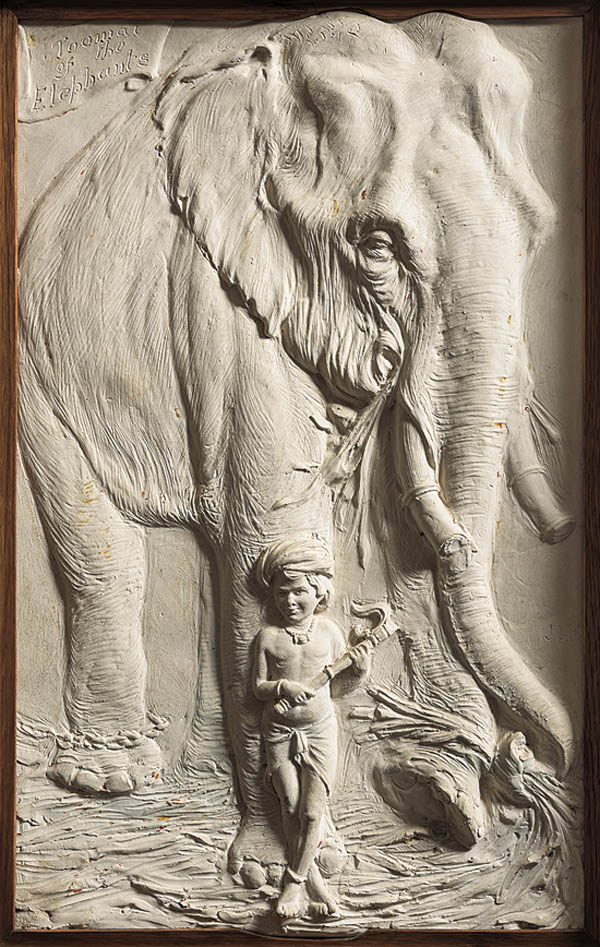

The Bard Graduate Center in New York has a tradition of exhibiting the work of influential but forgotten designers. Last fall, there was one organized in conjunction with the Victoria and Albert Museum in London about Kipling in India. No, not that Kipling, not colonial studies bogey Rudyard, notorious for composing "The White Man's Burden." It was his father, John Lockwood Kipling (1837-1911), artist and teacher, whose life and career were on view. Lockwood was the son of an itinerant Methodist minister on the provincial circuit. The family moved nine times in 24 years. He was educated at a Wesleyan academy on the assumption he would follow in the same path. That changed in 1851, when he visited the Great Exhibition in London. It was the first World's Fair, and hundreds of thousands of objects were on view. Of the more than six million visitors, few were more affected than young Lockwood. The Indian Court, an opulent showcase of "rubies, diamonds, pearls, vessels and chairs of gold and silver" (to quote from one guidebook), had a thunderbolt effect. He was spurred to dedicate his life to Indian art. So successful was his resolution that before he was 30, he was working in India as a sculptor and teacher. But first came the training in the Staffordshire Potteries. Beginning in 1852, he apprenticed with Pinder, Bourne and Hope, a manufacturer of transfer-printed wares. At the same time, he took classes at local design schools. He studied modeling and sculpting under artists who were applying historic styles to contemporary wares. In 1859, he was employed as an architectural sculptor in London, where he worked on government and ecclesiastical commissions in the prevailing Gothic Revival. ("Gothic was your only wear," Lockwood recalled in a speech more than 40 years later.) Then he was hired by the South Kensington Museum to decorate the new building. Lockwood, who was one of many Potteries-trained workers in the museum's decorative studio, distinguished himself. He was credited with modeling much of the terracotta ornament, including the panels of plants and animals. The South Kensington Museum, which was renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1899, was more than a collection of objects. It was a government department under the direction of the Board of Trade and was established to educate designers and craftsmen as well as raise public taste. A "National Course of Art Instruction" was taught in art schools under the museum's direction. Lockwood's design education was passed in these establishments. In 1865, Lockwood's ambition was realized. He embarked for Bombay to teach ceramics and architectural sculpture at the Sir J. J. School of Art and Industry, which was established to encourage Western art in India. It was his luck to have a wife on board for the adventure. A couple months before, he was married to Alice Macdonald, a quick-witted, literary lady with ties to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and Arts and Crafts Movement. One of Alice's sisters married Edward Burne-Jones, and another married Edward John Poynter, also a painter and future director of the National Gallery in London. William Morris was a friend and even had a nickname for her, Lady Alice de la Barde. For his dining room at Red House, Alice embroidered a panel based on Chaucer's "Legend of Good Women." It was executed according to a historic shading technique personally imparted by Morris. There were parties with Rossetti and Ford Maddox Brown. It would have been natural for her to settle permanently in this milieu through marriage. She came close a few times, with poetry usually the basis for these inconclusive engagements. When Alice was 26 and veering toward spinsterhood, she met Lockwood. They had much in common, including the austere and peripatetic Methodist upbringing (her father was also a minister). Both were acutely observant, a quality that was parlayed into a profitable journalism sideline. Moving to India was a solid career move that enabled the impecunious couple to marry less than two years after meeting. In Bombay, they lived in a bungalow across from the school, which was housed in "wigwams" (Lockwood's phrase) made of bamboo, palm leaves, and cow dung. Seven months after their arrival, Alice gave birth to Rudyard. The servants sacrificed a goat during the prolonged labor. Her biggest regret, looking back: "I ought to have met John earlier." Bombay was a boomtown with many Western-style public buildings under construction. For the Gothic city market, Lockwood and his studio created the tympana peopled with sari-clad women and loin-clothed men. For a hospital in the same style, they supplied roundels with turbaned heads. Lockwood was fluent in Gothic, and thanks to the South Kensington training, he knew how to adapt and modernize the design vocabulary of medieval Europe. In 1875, he was hired to be principal of the Mayo School of Arts in Lahore in the Punjab (today Pakistan). Bombay, which was founded on the coast by the Portuguese in the 16th century, was the most Western of Indian cities, although barely more than one percent of the inhabitants were Western. By contrast, Lahore was upcountry. It was an ancient walled city with a rich history of art and craftsmanship. It was reached by a long train journey. "Fire carriages" (the native term) rolled along at around 20 miles per hour with frequent delays. The first class compartments had toilets and sometimes baths. There was also a servant's room, so there was someone to look after the luggage and procure food and drink. For cooling, damp grass mats were hung in the windows. Surely, the Kiplings went first class. Second class was for servants and Anglo-Saxon riffraff (Hindus and Muslims complained about having to travel with such people). Third and fourth classes, locked and packed carriages with no toilet, were unthinkable. Lockwood's mission in Lahore was an about-face. Here he was to revive local artisanship and discourage Western influence. With the hereditary transmission of historic techniques in decline, the Mayo School of Arts stepped in to preserve the native heritage. It was an example of the British trying to solve a problem that arose, or at least was intensified, from the British presence in India. Part of Lockwood's pedagogy was Western. The curriculum included English language, geometry, and architectural and technical drawing. The study objects, however, were Indian. As he wrote in one of his annual reports, "The first thing to study is the actual work of the country, which alone can give a rational point of departure for variety of design and improvement of technique." This meant putting away the Greek and Roman plaster casts and ignoring the judgment of a compatriot critic of Punjabi art: "The great curse of India custom." Lockwood believed in custom. In any case, he believed in artistic custom, even if its perpetuation required overriding social custom, specifically the caste system, which placed handiwork at the bottom of the hierarchy ("the shabby genteel prejudice against manual labor"). Finding students of the right background, bright, perceptive, intellectually curious, and willing to disregard a millennia-old system of social stratification was an ongoing challenge. In his pursuit of a pure native aesthetic, he did not hesitate to object to the choices of the Indians themselves. He judged the European-style palaces commissioned by Indian princes a "deplorable error" on the grounds that "the architecture of the future in India must be of the indigenous styles." Lockwood was an Englishman among Indians, who in turn were divided by caste and religion. Some of the reports note how many Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and native Christians were enrolled for that year. He was also director of the Lahore Museum, with responsibilities akin to those of a 21st-century diversity coordinator. A display of agricultural figures was criticized for representing only Muslims, so Sikh figures were commissioned. Lockwood's teaching and administration were within the South Kensington framework, including the exhibitions of student work. The first he helped to organize took place a few months after his arrival in India. It was held in the train station at Nagpore, a city located in the same province as Bombay. Others followed in Poona, Simla, and Calcutta. Many were "universal," which is to say the fine and decorative arts were shown along with an assemblage of livestock, machinery, and European manufactures. The exhibits were a world away from the fabled riches of the East that captured Lockwood's imagination at the Crystal Palace. There were also contributions to world's fairs as well as specialized exhibitions at the South Kensington Museum. These overseas events were the opportunity to showcase for a Western audience the native arts that Lockwood wanted to insulate from Western contamination. It was one more tension embedded in his mission. Lockwood's work as a sculptor decreased during these years, but he found time to paint and draw. His drawings of Indian craftsmen were exhibited at the South Kensington Museum. They were precise visual documents of the weavers, carvers, and potters whose skills Lockwood studied and sought to perpetuate. In another vein, he addressed the frustrations and mishaps of housekeeping with native servants. The drawings were in the tradition of English caricature with the age-old abuses of toping and pilfering carried out by head boys (butlers) and maties (footmen). The drawings were the basis for a set of a dessert plates that would have been very much an "in" joke for the British when they were exhibited locally. Domestic life was also shown in the intimate sketches that flowed from his pen and illustrated his letters. The weather and transportation were popular subjects. In one, Alice is shown wearing a netted hat and holding a parasol, carried in a chair by bare-legged, sandal-shod indigenes. Victorian sketchbooks abound with such scenes of sustained respectability in the heathen land. In Lockwood's hand, they were conventional experiences expertly portrayed. The range of Lockwood's impressions was recorded also in his writings. He was a frequent contributor to the English-language press, with Alice as sometime ghost and regular unnamed source. Lockwood in his own words makes for bracing reading. He was a man of his time. He courted his wife with Browning. He had religious doubts. He marveled, "Considering the original texture of the native mind, it is wonderful how nearly well they work." There's more. A guidebook that he co-wrote with an English civil servant includes this observation: "Naturally, the Punjabi is somewhat clumsy and unhandy when compared with other races." Here's another doozey from the same source: "The number of blind people at Lahore is wonderful. This arises in great part from glaucoma." His reporting registers the changes wrought by the British in a short time. He was susceptible to the Punjab's melancholy-inducing decay and enjoyed exploring the lanes and byways of old Lahore, taking in the local color. The local odor was addressed by British sanitation engineers, who installed a drainage system. At other times, his tone was boosterish ("The Punjab has a great commercial future before it"). This reflected modernization in the form of urban planning with public gardens, a racecourse, and concert hall as well as a Central Mall that attracted European hotels and shops. Infrastructure meant railways and sewers. In India, the British literally drained the swamp. The result was better disease control, of which the Mayo School of Arts was an indirect beneficiary. Lockwood's reports occasionally mention the death from cholera of a promising artisan, and one year (1881), the student body was decimated by the disease. It wasn't just sensitive, questing types like Lockwood who felt the difference. One clear-eyed chief commissioner noted a tradeoff. On the one hand, "The aspect of the streets is less gay and brilliant." On the other, "An era of solid comfort and sanitary cleanliness had commenced." It took a comparatively small number of Britishers. The 1875 census of Lahore counted around 1,700. Lockwood and Alice's place in this community was uncertain. There was Lockwood's profession. He was a school principal in a country where the usual routes to success were church and army. There was, too, the lack of money. Hence the journalism, which in turn revealed their attitude to society. Invitations were accepted not to ward off homesickness but to get copy. Let it be added that many of these spectacles and amusements for the inhabitants of the empire's outposts, an exhibition of Old Masters copies ("really very interesting and good"), a freak show with "a very curious dwarf," would have been an agony for Lockwood and Alice. Alice, with her simple artistic dress and strong opinions on aniline dyes, was not like the other memsahibs gathered around the tea table. A contented, self-sufficient couple, they were further set apart by a complicated jokiness. For a fancy dress ball, their marriageable daughter wore a gown inspired by a type of regional Punjabi pottery. Lockwood retired in 1893, and he and Alice returned to England. They lived in a country cottage with a garden studio where he modeled Indian scenes. Always ready to mix things up, he based them on the Italian Renaissance reliefs recently acquired by the South Kensington Museum. He illustrated books (including Rudyard's) and was advisor to fashionable decorators. Lockwood and Alice died two months apart. He achieved his Indian ambitions, though he never questioned why he was in India. Ambivalence was for a later generation. He was a Victorian, who forged a productive life that combined adventure with moral purpose. For Further Reading Aijazuddin, FS. Lahore: "Illustrated Views of the 19th Century." Middletown, NJ: Grantha Corp., 1991. Bryant, Julius et al. "John Lockwood Kipling: Arts and Crafts in the Punjab and London." New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017. Kipling, John Lockwood. "Lahore As It Was." Lahore: National College of Arts, 2002 Satow, Michael et al. "Railways of the Raj." New York: New York University Press, 1980. Talbot, Ian. "Colonial Lahore: a History of the City and Beyond." Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

SHARE

PRINT