The Red Earthenware Manufactured In River Edge, New Jersey

A Look At Bergen County Pottery

By Justin W. Thomas - January 08, 2021

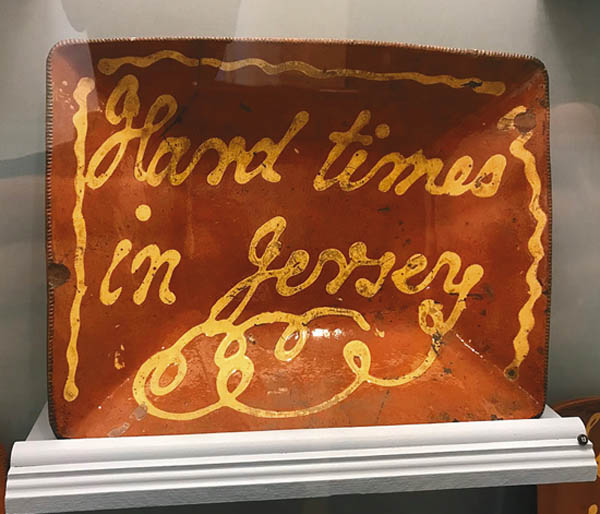

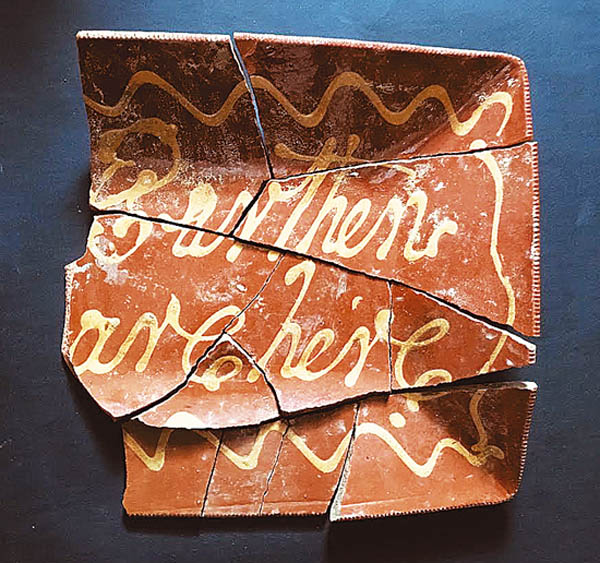

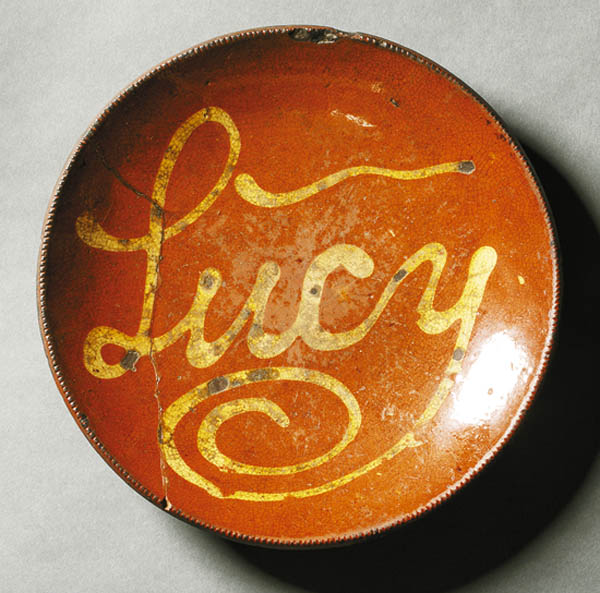

Founded in 1902 by northern New Jersey men and women, the Bergen County Historical Society tells the countys story as a whole, beginning with the areas settlement in the 17th century and through the 1900s. Since 1939, the historical society has been based at historic New Bridge Landing in River Edge. The museum is the largest historical society in New Jersey, while also representing the most comprehensive collection of artifacts illustrating the history of Bergen County, the New Jersey Dutch and other groups who settled in the area. Located across the Hudson River, about 16 miles north of Manhattan, and along the Hackensack River, River Edge was first settled by Europeans when Cornelius Matthew arrived, a Swedish immigrant who established the first settlement about 1683. In Colonial times, this area was known for its river crossings, farms and military activity that occurred during the American Revolution. Although, River Edge also sustained a prosperous red earthenware business in the 19th century, where some production can be misinterpreted for wares made in Pennsylvania today, some of which are owned by the Bergen County Historical Society. River Edge Red Earthenware New York City was a hotspot for potters who shipped their production to the citys docks in the 1800s; among the notable potters was a business established in River Edge by Henry Jacob Van Saun (d. 1829) about 1811, when he opened a brickyard and a pottery. Van Saun certainly produced all the traditional forms of utilitarian red earthenware, but his most significant wares may have been those manufactured around 1824-25, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the American Revolution and the return of Lafayette. Beginning in September of 1824 through July 1825, Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834) made a tour of the 24 states in America, arriving at Staten Island on Aug. 15, 1824. He toured the northern and eastern states in the fall of that year, including Thomas Jeffersons estate Monticello in Virginia, as well as visiting President James Monroe at the White House. Nearly 50 years earlier, Lafayette, a French general, led troops under the command of Gen. George Washington in the American Revolution. And among those who celebrated Lafayettes grand return were American potters; for instance, there were some slip-script red earthenware plates and platters manufactured, reading, Lafayette, such as examples that were produced in Norwalk, Conn., ca. 1824-25. Lafayettes return was the talk of the nation, and there was a demand for novelty items capturing this historic event. Van Saun decided to commemorate the event by manufacturing some plates with profiles in relief in the center, while Lafayette traveled through Bergan County. The few known examples include Lafayette, as well as Washington surrounded by 13 stars. These were likely manufactured for the local market, but some may have made their way into New York City in the mid-1820s, as well. The Bergen County Historical Society and the New York State Museum in Albany own the majority of the known examples today. But there must have been other styles also produced, seeing that I acquired a plate from this brand of production nearly 20 years ago at a small country auction in Dover, N.H. Like the other examples, this plate shows a profile in the center of a bearded man, also surrounded by stars. Van Saun may have also produced some slip-script during this period, even though there is little, if any evidence of this production. There is a known slip-script plate inscribed George that was found years ago in the Bergen County area; the thought is that the script represents George Washington. The technique seems more related to slip-script manufactured in the Bergen County area instead of Long Island, Connecticut or Pennsylvania. Sadly, though, soon after these plates were manufactured, Van Saun died in 1829, where his estate included $116 worth of brick, $189.23 worth of pottebakers ware, and pottery machinery, Cart and sundries valued at $37.50. Interestingly, he also owned a Schooner, Fanny Mariah appraised at $500, as well as a sloop, John Henry appraised at $1,500. These ships were likely used for transporting the wares by way of the Hackensack River, especially to the New York City market and other coastal communities. However, River Edges production did not end with Van Sauns death in 1829. The wares that are most recognizable from this area today are likely those that were made by George Wolfkiel (1805-67), who was born in 1805 in Franklin Township, Chester County, Pa. He was likely a Pennsylvania trained potter when he arrived in River Edge sometime around 1830, eventually purchasing the old Van Saun Pottery in April 1847, manufacturing red earthenware and some stoneware until he died in 1867. According to the book, History of Bergen County, 1630-1923, Volume 1, written in 1923 by Francis A. Westervelt (1858-1942), From Pennsylvania in 1830, came George W. Wolfkiel to Bergen County to establish his Pottery Bake Shop. There is a possibility where the place he located was already established, as it is evident he began his work at once. Wolfkiel was a master of his art; among his first orders was a wedding gift for a bride at Ramsey (N.J.) in 1830, consisting of a set of cups and saucers. One still in evidence shows they were greatly appreciated when she learned they were made of Bergen County native clay. This potter became well known, and his wares were carried by horse and wagon all over Bergen and Rockland counties and sold to country stores and to private parties. Wolfkiels production combined a wide variety of slipware, often adorned with initials, names, dates, birds and abstract designs. The most famous of the wares he made is likely a slip-script platter in the collection of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Conn., reading, Hard Times in Jersey. Another significant object made by Wolfkiel is a dated slipware plate, 1848, which is in the collection of the Bergen County Historical Society; the date may be related to Wolfkiels first full year of owning the old Van Saun Pottery. The historical society also owns a slip-decorated plate of significant interest that could be mistaken for wares made in Pennsylvania because of the style of the slip. But it is actually recorded as having been purchased brand new from the Wolfkiel Pottery in 1840 by A. Auryansen. Although some of Wolfkiels production was sold locally and elsewhere in New Jersey, archaeology has also proven that he shipped production to New York City, based on artifacts recovered in Manhattan and Staten Island. For instance, a slip-script red earthenware platter was recently recovered from a brick-lined privy at 33 Van Duzer Street on Staten Island, where the context of the privy dates between 1835-45. A merchant probably used this object as a means of storefront advertising, seeing that it reads, Earthen Ware Here. However, it does not necessarily indicate the merchant was exclusively a retailer of local earthenware; they probably sold all types of earthenware that was regularly shipped to New York City and the surrounding area in the 1800s. The style of the slip-script found on this advertising platter is similar to the platter owned by the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, inscribed, Hard Times in Jersey. The slip-decorated wares most identifiable to Wolkiels production are typically decorated with a distinctive curly Y, such as an example owned by the Staten Island Historical Society, retaining a history of local ownership, inscribed, Lucy. Another slip-script plate, manufactured with the same distinguishing curl, is in the collection of Winterthur Museum in Delaware, inscribed, Mandy; a group of related plates are also owned by the Bergen County Historical Society. A notable object that may have been manufactured by Wolfkiel was recovered not long ago about nine miles west of River Edge in Paterson, N.J. This fascinating slip-decorated red earthenware plate is adorned in a highly unusual stylized slip design, utilizing dots and squiggled lines, covering the entire plate as a canvas. Another extraordinary slip-decorated plate possibly made by Wolfkiel was recovered some years ago in Manhattan, where the remains show what appears to be a flower or some type of figure in the center, surrounded by a squiggled line around the exterior edge of the plate. This type of exterior slip design is found on some of Wolfkiels known production. Another market that this production was likely shipped to was Newark, N.J., which saw a giant increase in its population growth from when Wolfkiel first arrived in the area in 1830, of nearly 11,000 people to almost 72,000 people in 1860. In fact, found in the collection of the Newark Museum of Art are some objects that are attributed to Wolfkiel, retaining histories of ownership in Bergan County. Those pieces include a covered jar, which is a style of production that could be misinterpreted for production from another location, as well as a slip-decorated plate, formerly owned by the Bergen County Historical Society. However, there does not appear to be much evidence to suggest that Wolfkiel produced wares beyond single colored slip-decoration, although there is a known two-color slip-decorated red earthenware plate that closely resembles some artifacts recovered in New York City, and the style of the slip is comparable some of Wolfkiels production. But aside from red earthenware, Francis A. Westervelt also published that Wolfkiel made some stoneware, especially in the latter years of his career in the 1850s and 1860s. She mentioned one style of particular interest when her book was published in 1923, stating that he made, salt-glazed crocks decorated in blue with the American flag and his signature In Retrospect It should be noted that Van Saun and Wolfkiel were not the only red earthenware potters employed in Bergen County in the 1800s; other documented potters include Isaac V. Machett and his son, Jacques Mirgot, along with Peter Peregrine Sanford. Nevertheless, Van Saun and Wolfkiel are the most recognizable today, largely because of archaeology collected at the site of the pottery in 1902, owned by the Bergen County Historical Society, along with surviving objects retaining strong histories of local ownership, also in the historical societys collection. It is important to recognize that these men were not just local potters. For years, they found a niche in the ultra-competitive New York City market alongside wares made by the much larger red earthenware industries in Connecticut, Long Island and Philadelphia. Not only does this validate the significance of this production and the constant demand based on New York Citys booming 19th century population, but it also demonstrates the success, business savvy and skill of these important early northern New Jersey potters. Sources: Fitzgerald, Irene, Betty Schmelz, Charles B. Szeglin & Kevin Wright. The Tree of Life: Selections from Bergen County Folk Art. Bergen County Historical Society, 1983. Thomas, Justin W. The Red Earthenware Available in the 18th and 19th Centuries in New York City. Maine Antique Digest, October 2018. ___________________. Early Red Earthenware & Stoneware Found on Staten Island. Antiques & the Arts Weekly, January 31, 2020. ___________________. A Look Inside the NYC Archaeological Repository for Citys Earliest Pottery. Untapped New York, April 30, 2020. Westervelt, Frances A. Johnson. History of Bergen County, New Jersey, 1630-1923, Volume 1. New York City: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, Inc., 1923. Wright, Kevin. Potters Along the Hackensack River (Bergen County) 1805-1867. Bergen County Historical Society, 1983.

SHARE

PRINT